Aesthetics: How We Experience Magic (Free Excerpt from The Pages are Blank)

By Michael Feldman - Monday, September 18, 2023

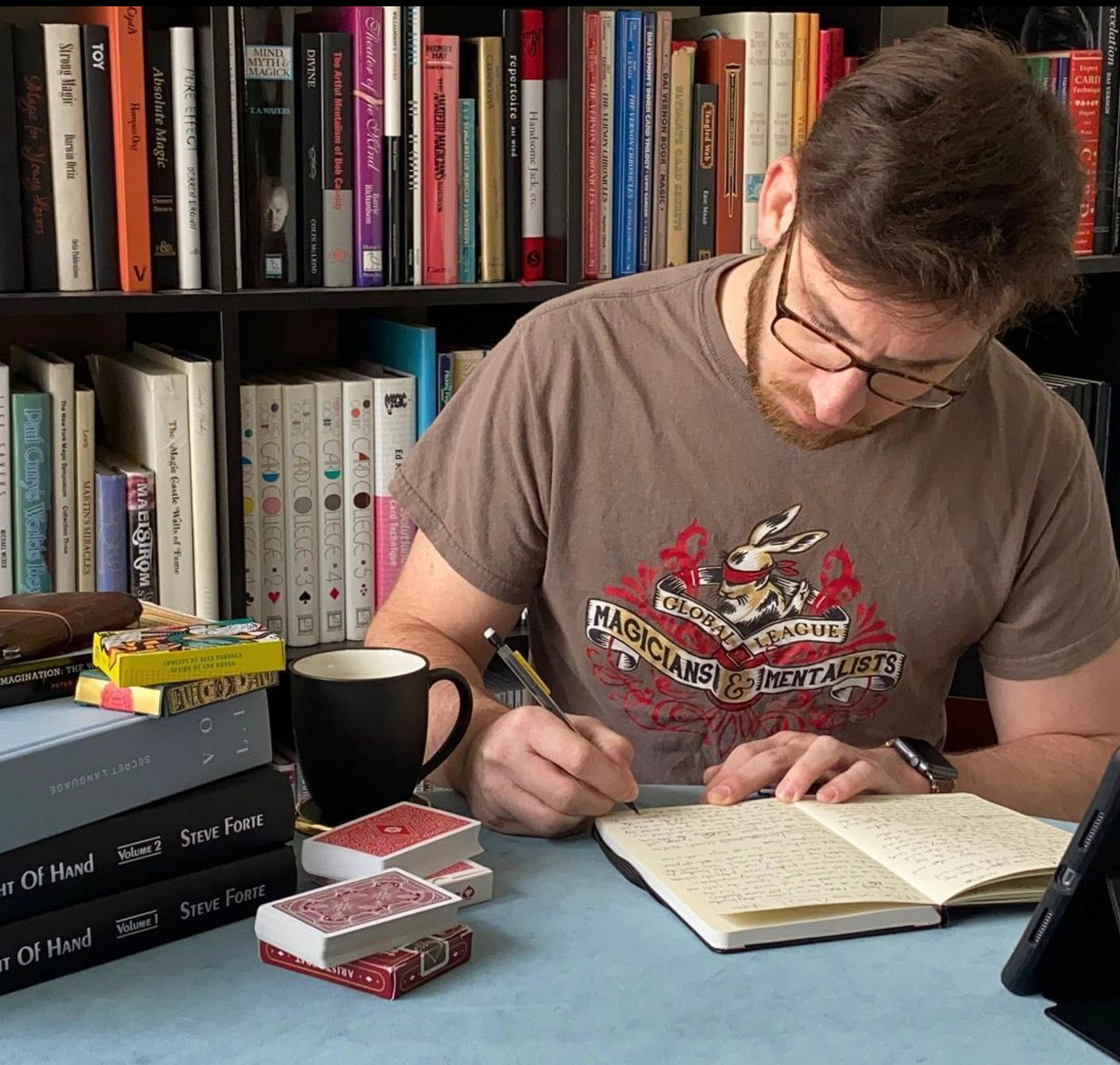

In his new book, The Pages Are Blank, Michael Feldman shares nearly 20 of his most cherished routines. Each original effect is structured around his unique approach to magic that helps audiences feel genuine moments of astonishment. Learn more by reading the intro to The Pages Are Blank below for free!

People know magic isn’t real. That’s why they seek out magic shows: to walk in with an understanding of impossibility and to walk out having somehow seen it happen.

If it was possible—if it was real—it wouldn’t be magic. It would be something more like science: maybe amazing, definitely possible. Demonstrating the amazing-but-possible can captivate audiences in its own way, but I’m after something different. I’m a magician because I find more room for creativity and self expression in the unknown and the impossible than in the known and possible. I want people to leave my performances more curious about their world. Magic is beautifully suited to this by making people question the reliability of their perception and the limits of understanding. Science provides an audience with answers. Magic provides them with questions. But it doesn’t work unless the audience understands that they’re being deceived. Knowing that magic isn’t real is critical to appreciating it as magic.

That realization has driven my aesthetic. I don’t simply admit that what I’m doing is sleight of hand. I focus on it. Reminding the audience they’re in a world where the laws of logic still apply forces them to confront the impossibility of the trick. Yes, it calls attention to the fact that it’s a trick. That’s the point. No amount of picking and finding cards will convince them magic is real1. But why would I want to? I don’t want my audience to forget it’s a trick. I want the idea of method to be front and center in their minds. I want them to grapple with what they’ve seen and struggle in vain for any satisfying answer. And I want their questions to survive contact with the internet. If I allow my audience to get so wrapped up in my fictional world that they accept magic is possible, I’ve sacrificed what makes magic unique: the absolute conviction they’ve seen something that they’re absolutely convinced is impossible.

This kind of magic also opens the door to sharing more of myself with my audiences. When I focus on the realities of being a magician, I get to share what I find fascinating and hope that curiosity is infectious. There has never been a more interesting time to study and perform sleight of hand. We focus on mystery at a time when we are more aware than ever of the scope of just how little of the universe we understand. We perform live at a time when our interactions are often designed, filtered, and manicured before we share them with others online. And we openly deceive in a time when it’s getting harder to tell the difference between truth and a mistake repeated so often that people have accepted it.

It’s also more interesting to admit that magic takes skill than to claim it’s real. People have become so used to the idea that their phones can do almost anything, they are amazed anyone takes the time to do anything by hand. On a trip to Toledo, Spain, I spent hours talking with the last person there who still forges swords by hand. He is incredible. In the middle ages, blacksmithing was a basic necessity. At the time it wasn’t appreciated as an art because it was essential to daily life. But today, huddled together with dozens of other people in awe of this blacksmith’s skill, we watch him forge a beautiful blade by hand. By medieval standards, my phone is sorcery, but today that type of sorcery is a basic necessity. I would much rather be open about my skill with cards than ask people to watch me pretend that I believe snapping my fingers has any effect whatsoever on playing cards.

Card tricks might be the least interesting use for “real” powers—if you could actually snap and wave and make anything happen, you’d be an idiot to use them to find chosen cards. But sleight of hand is a bizarre and fascinating way to fritter away your time on this planet. Who spends days, weeks, or months locked in a room figuring out how to convincingly not shuffle a deck of cards? Apparently, I do. You probably do, too. So lean into it. Explain to your audiences how bizarre it is to hone your skills just to keep them hidden purposefully. Demonstrate how desperately people seem to cling to their convictions considering how easy they are to deceive. Create effects about the challenges of performing live rather than from behind the safety of a camera and post-production. Magic can be more than just a string of arbitrary impossibilities.

Of course, openly emphasizing sleight of hand is not the only way to present compelling magic. It’s just the one I’ve chosen. First, let’s talk about what makes magic compelling, whether presented as real or not. Then, we can talk about why I chose the style you’ll see in this book.

Compelling magic—indeed any compelling art—relies on strong choices. Make a strong choice and get a strong reaction. Hedge, and the audience will be non-committal, just like the presentation.

Start with, “I hate card tricks,” and you have the audience’s attention. It takes a clear point of view. It’s unexpected. It makes the audience curious. They’re going to be intrigued.

Start with, “Do you have a strong imagination?” or, “Would you like to pick a card?” and you lose them. It’s cliche. There’s no clear point of view. They’ll probably tune you out until you get to the point.

The most common form of “hedging” in magic is “leaving it up to the audience.” Magicians so frequently debate the ethics of presenting magic as real, we know coming down on one side could alienate the other. What if someone disagrees? What if someone hates it? Well… they might. Hedging and vagueness usually come from fear of that judgment. But trying to please everyone often means removing anything that could provoke a reaction. Then it pleases no one. If I take a strong stance, I risk a strong negative reaction, but If I don’t take a stance, I won’t get much of a reaction at all.

Leaving it up to the audience to decide isn’t a real compromise. It’s indistinguishable from presenting magic as real. Of course the audience will assume you’re presenting it as real. What else are they supposed to think? You performed something apparently impossible. If you don’t give them another way to think about it, they’ll take it at face value. Every person born in the last century knows the snake-in-a-can-of-peanut-brittle gag. But when you hand someone a crappy plastic can labeled peanut brittle, you’re not “leaving it up to them to decide.” You’re claiming it’s peanut brittle. Being coy about whether magic is real is like handing someone a can labeled “magic.” They won’t assume that it is real. But they’ll assume that’s your claim.

The “snap and wave” is similar. It’s not hedging, but it’s vague. It’s not quite as cringeworthy, but it’s useless. It’s the magician’s equivalent of “um.” No magician has ever successfully convinced an audience that snapping causes real magic. It’s an arbitrary gesture. It distracts from the magic because audiences know it isn’t real and it provides no story to care about. They can simply tune out until I say something interesting. The same is true for waving, blowing, tapping, or any other gratuitous gesture, moment, or incantation. If the magic itself is fooling enough, they might be impressed in spite of a vague presentation. But why make a choice they’ll have to forgive when I can make a choice they’ll enjoy?

There are, of course, examples of magicians who have found ways to present magic as “real” that still feel authentic. Jared Kopf comes to mind. So does Garrett Thomas. They present magic as real, but they do more. They recontextualize what “real magic” is. Magic becomes a kind of metaphor for the intricacies of human interaction that we can’t explain. They remind us of real-life experiences and demonstrate how similar those experiences are to what we usually think of as “magic.” Gabi Pareras offered “fictional magic,” asking audience members to step voluntarily into a fictional world where magic is possible2. Andy from The Jerx suggests the “reverse disclaimer,” creating a story that is so clearly fake that no audience will take it seriously or feel the need to analyze it critically3.

The key to this style is commitment. Unflinching, uncompromising commitment. With 110% effort, I can appreciate the fictional world Jared, Garrett, and Gabi create. Any less, and I cringe. It’s harder to suspend disbelief for magic than for other theater. Most theater benefits from the “fourth wall,” the conceptual separation between fiction (the story on stage) and reality (the audience watching people pretend). Magic doesn’t have that. Unlike an actor who comes on stage, answers to a different name, and pretends there aren’t a bunch of people sitting in chairs in a giant room all facing the same way, magicians generally walk on stage under their real name and speak directly to the audience. That requires far greater effort to suspend disbelief. The standard cut-and-paste presentations like, “I predicted this in a dream last night,” just don’t cut it for me.

For instance, a solid majority of mentalists have apparently had the exact same experience: the night before I saw their show, they each dreamt about a playing card, woke up, and wrote it down just in case someone in their next show thought of it. It feels ridiculous. Not hilariously ridiculous or interestingly ridiculous. Just run-of-the-mill patronizing. Am I supposed to think they have the same dream every night and twice on Sunday for the matinee? If they think that claim is compelling by itself, they’re dreaming. I have so many unanswered questions. Ok, you’re having weird dreams. Why are you sharing them with us? If your show relies on dreams, what happens if you don’t remember your dream? If you have prophetic dreams, isn’t it weird they’re about playing cards? In short, why should I care? Where’s the human connection? Without more, this kind of presentation feels more like an excuse to do a magic trick rather than a compelling piece of theater.

But even presented well, this aesthetic of “real magic” just isn’t for me. I prefer to focus on trickery for several reasons:

First, there’s no need for a fourth wall or suspension of disbelief. Because I’m not asking people to believe anything that isn’t real, there’s no need for that kind of fiction separating their reality from mine. Instead, it opens the possibility for genuine and engaging conversations. After all, I’m at a party or show and these are the topics I genuinely care about. Presenting magic as real requires a fiction that can get in the way of that connection. My style gets rid of that barrier by acknowledging the truth: I’m deceiving people.

Second, people genuinely care. After the show, they ask, “Do you ever mess up?” “Where did you learn your secrets?” and, “How long does it take to learn a trick?” No one runs up, eager to ask me what other powers I have, when I discovered I was “different,” or whether waking up from show-related dreams every night and twice on Sundays is taking a toll on my sleep schedule. Giving my audiences the chance to peek behind the curtain at how I create the show they see engages them and can answer the questions they may already be wondering.

Third, it’s a more modern approach. It gives me the opportunity to explore what it means to be a magician today. It allows me to explore deception, perception, and illusion alongside contemporary knowledge and science. Presenting magic as real is often deliberately old fashioned. It relies on the image of the magician as the keeper of ancient, lost knowledge. It harkens back to a time when people were more inclined to believe in magic (and when people still used words like “harken”). It paints magicians as the old guard, usually in conflict with contemporary ideas of knowledge and science.

Fourth, while it’s easy to fall into weak choices of presenting magic as real or “letting the audience decide,” admitting sleight of hand is almost always a strong choice. It’s unexpected. It’s intriguing. Popular culture has taught audiences that magicians are defensive about whether our magic is “real.” People who haven’t seen me perform often tiptoe carefully around the word “trick,” because they think magicians prefer to pretend their magic is real even off stage. Once they’ve seen me perform, they’re not surprised that I think quibbling about whether we “do tricks” or “perform illusions,” loses more respect than it wins back. It’s like an actor insisting that he’s still Hamlet after stepping offstage.

Of course, an engaging and non-patronizing presentation doesn’t have to be true. It just has to seem true. Thus, my favorite aesthetic: meta self-awareness. My Book The Pages are Blank takes its name from a particularly wonderful example from comedian Bo Burnham. In his comedy special, What, Bo Burnham takes out his notebook to read some poems. After a few, he turns the notebook to the audience and admits, “The pages are blank. I know them. Why am I lying to you?” People realize they’ve been fooled and they start questioning all the assumptions they’ve made throughout the show. What was true and what was planned? It’s a masterclass for magicians. He feeds the audience’s assumption by carefully turning the pages between each poem, then reveals it was always a ruse.

I love these moments in any art. They don’t just secretly exploit the audience’s assumptions for a joke or magical moment. They openly force the audience to confront assumptions they didn’t even know they were making. It’s a metaphor that is increasingly relevant in a time when truth is debated more and more. And it’s a metaphor magicians are particularly well suited for. But it’s only a metaphor available to magicians willing to pull back the curtain and admit to the reality of trickery.

Buy The Pages are Blank

More than fifty years ago, Vernon wrote, “[T]hey’ll assume it’s done by trickery anyway, because they know you’re a magician ... [Y]ou might have some people who are gullible enough to really believe that they’re witnessing real telepathy. But it’s very difficult.” Dai Vernon, The Vernon Touch: The Writings of Dai Vernon in Genii, The Conjurors’ Magazine from 1968 to 1991 (2006), pg. 47. Audiences have only gotten smarter since 1968. Andy from The Jerx put it this way: “If coming off as ‘real’ is a priority for you, then what you’re saying is, ‘I want to dupe dumb people and look ridiculous to smart people.’” Andy Jerxman, The Jerx, Volume 1 (2016), pg. 2.

Roberto Mansilla, “Fictional Magic,” Quarterly, Issue No. 2 Spring 2015 (2015), pg. 5.

Andy Jerxman, The Jerx, Vol. 1 (2016), pg. 1-26.

Back to blog homepage

Similar posts on the blog: