Howard Schwarzman: Wishes Fulfilled

By Jamy Ian Swiss - Thursday, August 27, 2020

I grew up in the community of Tannen's Magic. Lou Tannen himself taught me my first sleight of hand magic, and sold me my first important books — Tarbell, Lorayne's Close-up Card Magic — my copies of which are misprinted or otherwise damaged copies of Tannen's publications that Lou would keep in the back and sell to kids like me at a discount. Irv Tannen, Lou's brother (who called everybody "Kid"), let me come back again to see the Third Annual "Miracles of Magic" in 1969 at the Barbizon Plaza for free on the second of its two nights, where I saw, among others, Al Koran. Seeing him at the Friday night show, and studying his book in the weeks before the shows, I met Koran in the shop the next day and he gave me a memorable lesson. That same afternoon, Irv suggested I come by the theater that night, and I did, and he let me stand in the back with him to see the show a second time. I've written at length elsewhere about these and other priceless lessons.

In my teens and twenties I regularly attended the annual Tannen's Jubilee convention. I saw many of the great winning FISM acts; I saw Lance before he won; I saw Copperfield at age 19, the same year as the ABC special, "The Magic of ABC," that introduced the lineup of new ABC shows, and introduced David to the American television audience. To this day, when David and I occasionally cross paths or otherwise chat, we invariably end up talking about our days at Tannen's. One of the two nights I saw Koran at the Barbizon show, a very young David Kotkin — aka Davino — was called up on stage to assist him. A few years ago, David showed me Koran's prop briefcase, now housed within his collection.

At the Jubilees of my youth, I would dutifully, obsessively, attend every lecture, and many of the lessons I learned remain with me today, so many decades later, from the likes of Dick Zimmerman, Gene Anderson, Coe Norton, Howard Flint.

But the most important part of the Jubilee for me was the close-up shows. I would drag myself out of bed about 8:00 am on Saturday morning, in order to find a good seat in one of the five or six close-up locations scattered around Brown's Hotel in the Catskills, then wait until 10:00 when the shows would begin, with the likes of Goshman, Slydini, Dingle ... a panoply of legends.

So many lessons drawn from those performers — the names quickly multiply by dozens more in my memory — remain alive in me and in my work today, and as time goes by, I value them all the more. But now and then I recall even more precious gifts, the significance of which I lacked almost any awareness of at the time. The Jubilees were filled with memorable characters (of course!), and my days and nights there were filled with encounters that were surprising, funny, mystifying, and instructive. At my very first Jubilee, at which my father accompanied me, we were seated at dinner with the New York magic dealer, juggler, collector and raconteur, Larry Weeks. The first night at dinner, after initial introductions around the table, Larry asked my father if he would do him a small favor. Then he sort of wiggled in his chair, like a seated dance move, and asked my father if he would do the same. My Dad, ever game, did the wiggle. "Thanks," said Larry. "I always wanted to see a Swiss movement!"

When I think back and comb my memory for such moments, I can recall Jack Chanin, ever present, making a steel railway spike suddenly appear or disappear, or tear the center out of a dollar bill and eat it, only to instantly restore it. (The instructions cost a dollar and amounted to a typewritten page, but did not come with Chanin's epic personality and charisma, nor the Fez and exotic gold hoop earring he wore.) Bobby Bernard was always around, with his oversized spectacles, doing coin magic and, on rare occasion, tipping or critiquing something; when I got a compliment from him decades later after performing on stage at a UK convention, I was secretly thrilled.

I remember witnessing an epic late night showdown in the lobby between Derek Dingle and Michael Skinner, trick for trick, including a version of the Elevator Cards, all the rage at the time. I would learn Bill Simon's version from Effective Card Magic, but sadly missed meeting Simon, who was apparently often around a the Jubilees. I didn't meet Skinner that night, but eventually would, years later, come to know him as a friend and mentor, first introduced at an overnight session in Atlantic City.

All of this remains with me today, and I never thought to thank anyone at the time for these moments and experiences, because I did not recognize their importance, or the timeless value they would provide.

And I remember another ever-present face at those Jubilees. A short, loud, bespectacled, red-haired imp of a man, with small and excruciatingly skilled hands.

Which brings me, after an admittedly long prologue, to some thoughts about the passing of Howard Schwarzman.

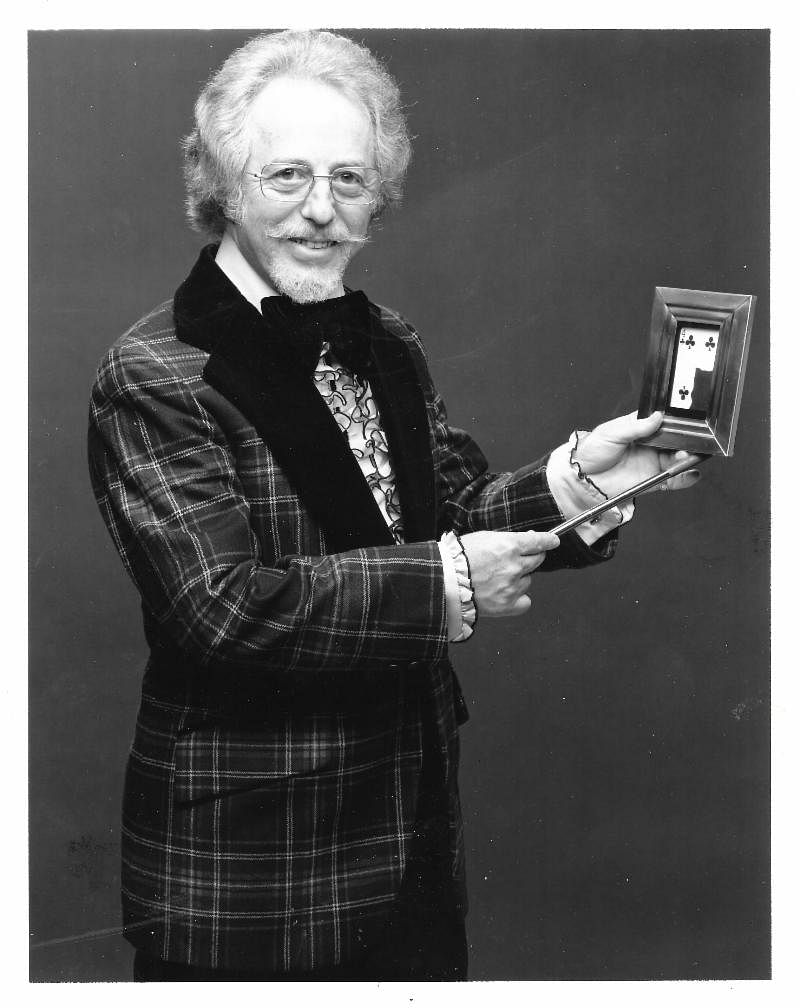

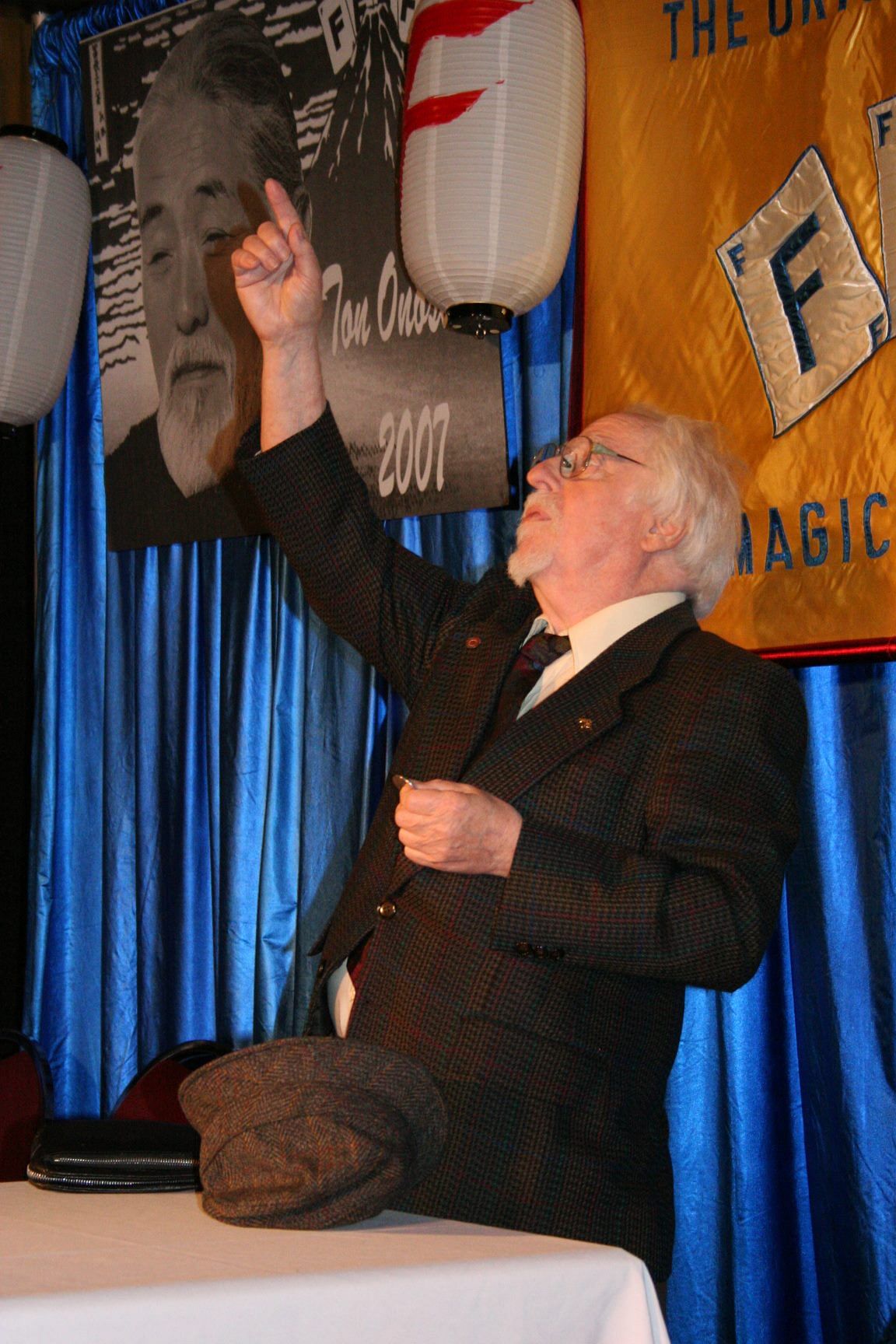

Photo by Dale Ferris

Photo by Dale Ferris

Back then, I was actually a shy kid, a full-blown introvert in fact, who rarely initiated conversations with all the marvelous characters and wondrous magicians I met at the Jubilees and at the Tannen's shop. I mostly remained quiet, but I watched, ever attentive. Howie, as everyone knew him, would have intimidated me back then, and he would not have particularly noticed or known me among all the other awkward adolescents. But he was a presence, a constant one, often having a table in the Jubilee dealer's room, and invariably was amid the innermost circles, alternately sessioning and cracking inside jokes. Back in the Jubilee days, I barely knew him at all, but I always knew when he was around, as he was invariably loud, and laughing, and doing tricks and moves. And occasionally, he'd talk to an awkward adolescent and maybe give him a tip, fix a move, or try to sell him a fancy little prop the kid could never afford. I can't say I had a relationship with him back then. I just knew he was there, part of a group to which I was a young, distant outsider.

Time passed. In 1980 or '81 I began attending the Fechter convention in Buffalo, where Howie was always a large presence, belying his small stature. He could be the most obnoxious of hecklers, always among the select front-row veterans with reserved seats, but he earned it with chops and expertise. Anyone who came to the Forks in those days knew Howie, and I slowly began to get to know him just a tad more. As I graduated into some of the late night suite hangouts at the Jubilee, I spent more time with him there, invariably learning card moves from him. I recall the night in one of those rooms when he showed me a subtle technique for getting a jog from a one-hand squaring of an inserted selected card. After he fooled me, then tipped it to me, he explained that it was Bill Simon's, sending me back to revisit that Simon book again. Books are important, but so are critical guides, to point your way along the path.

After years of attending the Jubilees, I finally abandoned them when the New York Magic Symposiums arose for several years, during the early 1980s, in New York City. These conventions were among the greatest I ever attended, and for a dramatically preferable change, they were focused on close-up magic. I saw a lot of great magicians there, whether it was in shows, lectures, or just hanging around the hotel bar, and they coincided with the early years following my career change to magic. By the time of the final Symposium, I had to take a break of a few days from my Magic Bartender gig at the Inn of Magic, in the Maryland suburbs of DC, in order to attend the convention.

I possess countless memories of the magic and magicians of the Symposiums; two of them involve Howie Schwarzman. In one instance, a sizable group was gathered in a lobby lounge area, where the legendary Charlie Miller was seated, surrounded by those of us thrilled to make his acquaintance for the first time. Various younger magicians were approaching Charlie, to ask a question, or show him something and seek an opinion. Eventually, my pal Geoff Latta approached, and asked if he could show Charlie a pass. Miller was a legendary pass expert and critic, and the stories preceded him, enlarged by many accounts from Vernon, of Miller's inclination to closely examine a shift from every angle, even lying on the floor to view upward from beneath, before pronouncing an oftentimes critical opinion. Latta was gaining increasing renown in the underground for his extraordinary Riffle Pass at this time, in addition to his coin work, and it was a big moment, which he and I had discussed and planned with anticipation, to put it in front of Charlie Miller.

Latta began to demonstrate. Charlie asked to see the move again, and asked a question or two. Howie was seated nearby — a longtime acquaintance of Miller's, and who also knew Geoff — and he began to raise an objection, complaining about the movement of the riffle action. "But you don't need that!" But Miller shushed him bluntly. "Shut-up, Howie!" waving him into silence with a gesture. Charlie was interested in what he was seeing.

And just a few moments later, after a few more quick demonstrations from Geoff, Charlie made what was clearly intended as an unarguable pronouncement to all who were within earshot. He looked up at Geoff and said, simply and firmly: "Your technique is perfect."

But this story isn't intended as a knock on Howie. He had the credibility to chime in, and there were reasons he objected to Geoff's Riffle Pass, grounded in Howie's own work. But I will come back to that.

I mentioned having two recollections of Howie at that Symposium. Another also involved Geoff Latta. Somehow the three of us ended up at the base of a staircase, away from any other magicians. Howie showed Geoff and I a trick, and fooled us badly. Then when he tipped it, we were floored that we had essentially been fooled by palming. Among Howie's many technical strengths — and there were many, indeed — he was one of the finest experts at palming cards I have ever known. And as we stood with him, he gave us some detailed work on Vernon's "Topping the Deck," the first serious lesson that set me on the path of a decades-long fascination with this particular sleight, possibly the single most perfect sleight in all of card magic. Howie did it impeccably, and was the first to show me some of the real work on it. Later, years later, I would be fortunate to also see the move up close and in detail by two other masters of the sleight, John Thompson, and Harry Riser. I have been fortunate to have great teachers.

So while Geoff and I were certainly amused by Howie getting his notoriously loud mouth summarily shut down by the likes of Charlie Miller, it wasn't because we didn't respect him. We respected the hell out of Howard Schwarzman, a guy who knew, and did, the real work.

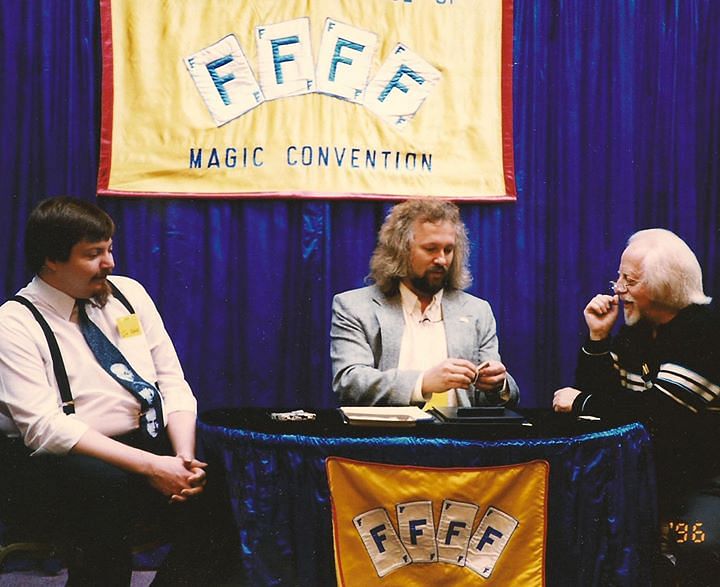

Jim Krenz, Antony Gerard and Howie at 4F 1996

Jim Krenz, Antony Gerard and Howie at 4F 1996

As I think about it now, I realize that I know the moment that I crossed over from being one of countless familiar faces to Howie, to one he would thereafter remember and call by name. And it would happen just a few years later, in 1985, at the Inn of Magic. It was mere weeks after I was hired for the job by Bob Sheets, and only days after I had moved to Wheaton, Maryland to become the full-time Magic Bartender at the Inn, which contained the world's largest Magic Bar and also a dinner theater that sat more than 300 at dinner roundtables and with a full proscenium stage for the magic shows.

It was opening night, in April, I think, of 1985. The bar was reasonably busy and everything was new and yet undiscovered. I was performing close-up magic behind the bar, and making some drinks here and there, backed by a couple of full-time bartenders. The bar sat something like 35 seats along it's length, along with two-tier wooden bleacher bench seating that sat an additional 150 or thereabouts. In the midst of a set, I noticed that Howie Schwarzman had come into the club. He was semi-local, living as he did in Baltimore, a veteran member of the Baltimore magic scene. I recall distinctly that I included my lengthy Ambitious Card routine in my set — an 11-phase routine in which half the phases are powered by some form of the shift.

When the set was over I made some drinks. Howie hustled to the end of the bar, where the service bar was, and called to me, waving me over. I was wary. I knew how obnoxious Howie could be, and frankly without effort. Truth be told (and I will return to this as well), this trait was unarguably a part of his reputation.

When I got close to him, he lowered his voice, talking shop while a loud drinking crowd of laymen were enjoying themselves immediately nearby. "Who taught you the pass?" he asked earnestly. I was a bit surprised at the unexpected question. "Well, from a lot of sources, but when it comes right down to it, it's mostly due to my friend Geoff Latta."

"Well," Howie said — insistent now in his demeanor — "There are a lotta guys around who talk about the pass, who think they can do the pass, and most of them can't." "That's certainly true," I acknowledged.

"You — you can do the pass."

Stunned, genuinely stunned, I thanked him for the compliment, and shook his hand. "That's all I have to say," he said, and walked away.

I hadn't thought about that moment for many years, but now that I recount it, the truth is that while I had been a full-time pro for several years at that point, jumping off that night into a new stage of my career, that was one of the greatest, and most surprising, compliments I had yet received as a magician. And as far as the pass goes, the only other one that matches it would eventually come from — it's true — Charlie Miller. But that's another story.

Howie with his Piper Cherokee, one of two planes (his other was a sea plane) that he often flew to magic conventions, sometimes with magician friends along for the reputedly white-knuckle ride.

Howie with his Piper Cherokee, one of two planes (his other was a sea plane) that he often flew to magic conventions, sometimes with magician friends along for the reputedly white-knuckle ride.

And so I got to know Howie, and when we crossed paths, at The Inn of Magic, at the various magic shops like Al Cohen's or later Denny & Lee's, at lectures or at magic conventions, we would always talk and often session. I'm not a great note-taker but in some cryptic 4F notes I have that are in digital form, I find one about a diner session with Howie where he showed me some table passes I can't recall, at least one that also was linked to a palm, and a gambling dodge from the fabled card worker, Artanis, that involved a second deal and draw poker, which I think I can recall.

There lays the essence of what you need to know, and that we all need to remember. Howie didn't just know a few things, or even a little about a lot of things — Howie knew a lot about a lot. In Vernon’s New York years, when New York City was the center of the magic world thanks to Vernon’s presence, and magicians would hang out at Holden’s, and the card stars would gather at Ed Balducci’s soirees, there were the typical handful of hard core youngsters desperately trying to earn their way into the inner circles. Among those youngsters were names like Kenny Krenzel, Herb Zarrow, and Howie Schwarzman. A generation later, when I was one of those youngsters, we would be hanging around the Tannen’s scene, and on Saturday afternoons when the shop would close at three, we would follow those guys – Krenzel, Zarrow, Wes James, and Lorayne and more, and Howie if he was in town — to the Governor’s Cafeteria in Times Square.

So Howie was the first hard-core Erdnase man I knew. He could do pretty much everything in Erdnase, particularly the palming and the shifts — every one of them, and the first I ever saw who could do the SWE Shift perfectly. (Later I would meet and see Harry Riser do it also.) He was the first truly great palm worker and shift worker I saw up close, along with Dingle — who, in his Collected Works, explicitly thanked Howie "for teaching me the pass," along with Krenzel for "explaining many of the technical refinements." Pointed along the path by those lessons, Dingle would revolutionize the use of the pass. And in turn, would inspire Geoff Latta to further advance the cause. The best have always had great teachers.

But that's only a piece. Howie was also the first I learned about Ramsay from, seeing Howie do Ramsay's Three Coins In the Hat. He was the first one I saw really use a Jack Miller holdout, which of course he had learned from Miller himself.

Yet for all his fascination and expertise with sleight of hand, Howie also loved toys — and he sold beautiful and mystifying and notably expensive ones. He had relationships with European dealers and creators — he always attended FISM — and he was an exclusive distributor for many years of many of the remarkable inventions of Lubor Fiedler.

So Howie understood a lot about a lot of magic, and I recognize now that I also learned lessons from him in subjects like misdirection, and theory. I remember him giving me this lesson, for example. "Cardini changed the effect of card manipulation," Howie explained. "Other magicians produce cards. Cardini changed the effect: he threw cards away." It was an important insight, one I have passed along on many occasions.

Over the years, I would lecture from time to time at Denny Haney's in Baltimore. It was the best lecture audience in America, because its members were mentored by Denny — a great magician but also a fabulous mentor, who took his role seriously. He taught his acolytes what was good, and made sure they came and learned lessons and paid attention, and also reacted and rewarded the performers and lecturers he booked for their continuing education. You were always treated well at Denny's and it was a pleasure to lecture for him and his group, but the price of admission was that Howie would sit on the side and heckle.

While I assume that on occasion that could really be a problem for some presenters, by the time those years came around, Howie and I knew one another, and respected one another, and he wasn't about to louse up my show. We would toss a few lines back and forth, I would pay him respect — which is ultimately what that was all about anyway, and why not — he'd legitimately earned that stature of the Village Elder. And Howie was free to toss out a suggestion or idea now and then, and those were usually well worth listening to. We laughed a lot. And I could still learn a few more of those lessons.

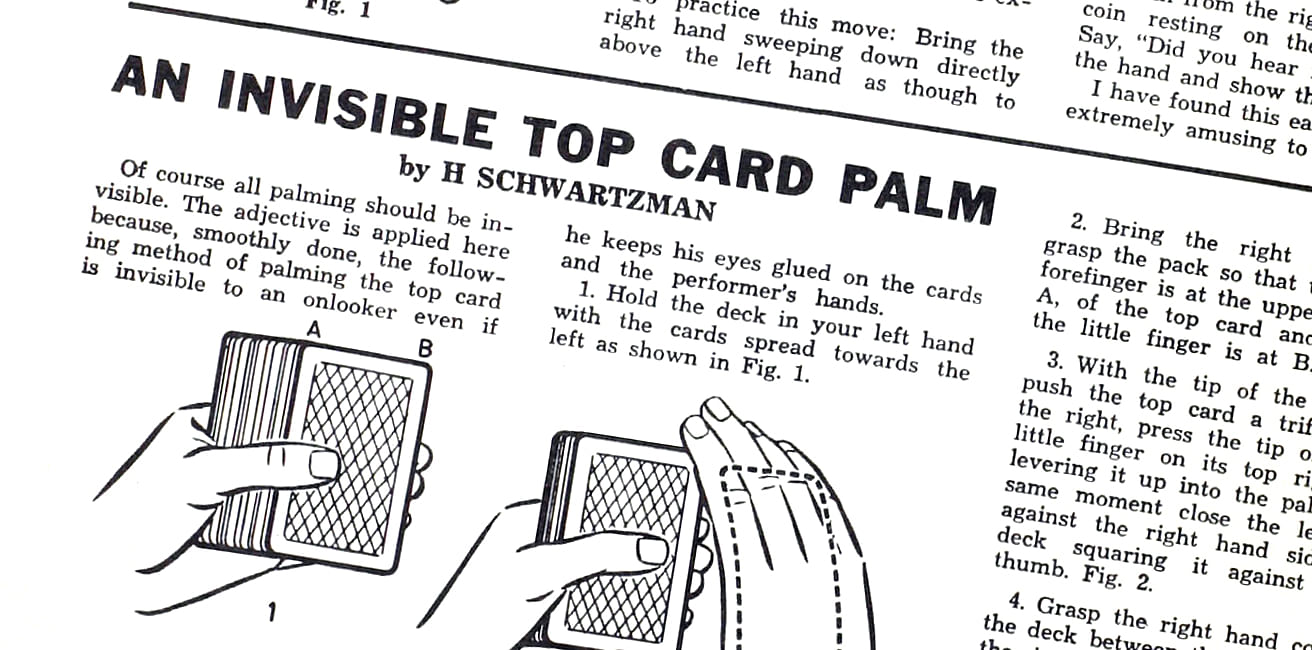

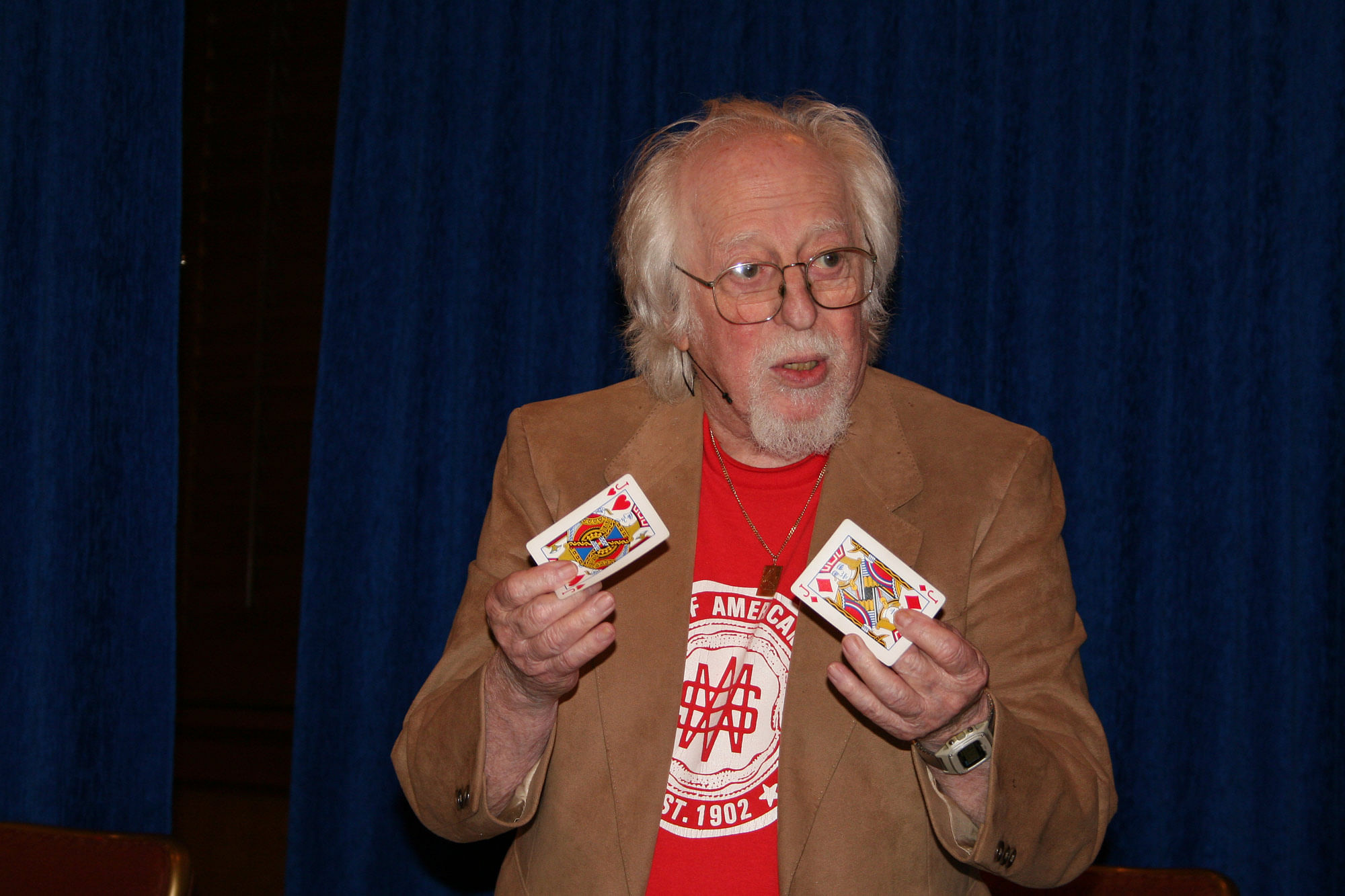

Howard's "Invisible Top Card Palm" from Hugard's Magic Monthly

Howard's "Invisible Top Card Palm" from Hugard's Magic Monthly

For cardicians, I want to draw attention to a few particular contributions Howie made to the craft of card magic, and drill down a bit on a particular example of his work and what it taught me.

If you go to Denis Behr's online Conjuring Archive and do a general search on Howie's name, you will promptly receive a substantial page of 64 items.

Among them you find multiple explanations of Howie's "Tilt Finesse," which has now become such a standard tool since its initial publication in 1975, it has been re-described numerous times since, as will be readily apprehended in the archive search results.

Another finesse, lesser known but no less significant in my estimation, is Howard's idea of allowing the deck to spread out of square prior to executing Vernon's "Topping the Deck" palm. I want to take a moment to discuss this further as it is widely overlooked and also somewhat misunderstood in its proper crediting.

First published as "Invisible Top Card Palm" in Hugard's Magic Monthly (Vol. 5 No. 4, 1947, p. 350), that description is somewhat primitive and does not make clear what was actually intended, which was (as Howie explained when he first showed this to me) as an addition to, and a starting point for, Vernon's "Topping The Deck" palm from Select Secrets. I could write a very long essay about this sleight, which I likely will do someday, but for my purposes here I will state that this is quite possibly, in my very seriously considered estimation, the most perfect, or at least the most close to perfect, sleight in all of card conjuring. It cannot be improved upon, however, Howard Schwarzman managed to create not an improvement per se, but rather an addition to the sleight that, once adopted, renders the execution of the sleight both somewhat easier, and even more deceptive.

Howie's technique of basically allowing the deck to tip out of square before initiating the Vernon move accomplishes several things. Firstly, it avoids the one problem of so many palming techniques, including those in Erdnase, of squaring a squared deck. Letting the deck fall out of square (or finding a reason to knock it significantly out of square by spreading, or by briefly looking at the faces, as I describe in Scripting Magic by Pete McCabe) resolves this unnatural, logical inconsistency.

However, Howard's addition accomplishes more than that. One of the many flaws in many executions of Topping the Deck is too much movement — i.e., too much pushing the top card over with the left thumb, too much of an angle jog of the card, too much movement of the right fourth finger in order to lever the card upward, too much movement in either or both hands in securing the card in palm position. Howie's finesse helps resolve the first item of this list. By allowing the deck to fall out of square, then simply resting the left thumb diagonally across the top card with the slightest hint of downward pressure, now as the right hand takes its position grasping the deck from above, the right fingers and thumb slightly tighten the deck into square — and the result is that while the deck comes to square, moving slightly leftward beneath the top card, the top card never moves at all, and is instantly left in perfect, slightly angle-jogged position as the first step in initiating the palm.

This may read like a minor fine point, but it is not. It is the final finesse that adds to the perfection of the Vernon move, which as I've already mentioned, Howie did exquisitely well, literally perfectly.

While poorly described in its initial publication in Hugard's, Schwarzman's technique was eventually re-described in Jennings '67 by Richard Kaufman. While the description is clearer and more detailed, it does not mention that this is really an addition to or a finesse for Vernon's Topping the Deck; also, the text claims that "the mechanics are different" than the original Schwarzman item, but I fail to detect any difference other than that it is a more detailed description of Howard's idea, exactly as he taught it to me.

Further considering the results of the Conjuring Archive search, one finds a number of non-card items. These include Star Warp, an innovative version of Card Warp using one card and a dollar bill (inspired by an idea of Bob McCallister's). Also included are several coin items, including the Instantaneous Coin Change from Bobo's Modern Coin Magic, in which a coin changes as it is casually and very cleanly tossed from one hand to the other. At the conclusion of "Presto: A Grand Master," my 18-page segment about New York magician Earl "Presto" Johnson in my book, Preserving Mystery, I describe what I have dubbed "The Really, Really Instantaneous Coin Change," which was Presto's handling of this innovative Schwarzman sleight. While Howie did the move casually, with the hands close together and a minimum of movement, Presto, extraordinarily, did the move one-handed: that is, in his signature routine for Spellbound, he would display a half dollar resting on the extended fingers of his palm-up right hand; then he would apparently toss the coin, one-handed, up into the air, where it appeared to change in midair, falling and landing on his hand now as a copper coin, in the same place the silver coin had begun. Presto could do this repeatedly, effortlessly ... astoundingly. I've never seen it done by anyone else, but someone is bound to adopt it again one of these days.

But of all the material in the published record created by Howard Schwartzman, my favorite is perhaps among the least well known. The card routine, "Night Visitor," was published in 1974 in Epilogue (Issue 21), and comprises a finessed handling of Larry Jennings' trick, The Visitor, in which a signed selected card travels invisibly, from being sandwiched between two reversed Queens in the midst of one half of the pack, to between the other two reversed Queens in the other half, and then back again when they began.

The Visitor is without doubt a neo-classic routine, and in the Seventies and Eighties it was a pet trick among expert card enthusiasts. Howie Schwarzman took this superb trick and, analyzing it move by move, retained the Jennings construction and effect, but expertly refined the piece into a sophisticated masterpiece of close-up sleight-of-hand.

I don't recall exactly when Howie sat me down and showed me this trick, but I suspect it was in the very late Seventies, or at the latest the very early Eighties, a formative period of my development as a technician and a technical thinker. This is the period when I changed careers, when I spent inordinate time with Geoff Latta, when I first got to know Michael Skinner. When Howie explained the details of his Night Visitor routine to me, he presented me with a new level of how to think about sleight of hand. The degree of detail and analysis Howard brought to his examination of the trick; the elements which he identified as problems that others had never noticed; the solutions he devised aimed at eliminating these flaws, thereby improving the piece and rendering it more deceptive, more elegant, more magical; and the degree of detail and logic, and technique, that he brought to the entire process, was literally consciousness expanding for me. It enlarged my view of what sleight of hand was and could be. Michael Skinner was another teacher who expanded my thinking in this way, when he would explain his analysis and reasoning about any trick that we discussed or that he would share with me. Howie's thinking was no different.

Without merely re-describing what is already in the pages of Epilogue, Howard's intention in redoing Jennings' Visitor was to — in the tradition of his own mentor, Dai Vernon — bring clarity to the plot, and cleanliness to the technique. After inserting the selection between the first pair of reversed Queens, instead of randomly cutting the three-card sandwich into its half deck with multiple cuts (which is to say, the Double-Undercut), Howie begins by clearly centering the three-card packet within its half of the deck; then he merely squares the pack, and executes a shift — thus leaving the audience with absolute clarity about where those two cards were located. Instead of now bringing the other pair of Queens over the first packet in order to steal the selection beneath, he immediately follows the shift by palming the necessary cards and transferring them as he retrieves the second packet. Capping the deck but retaining a break, so as to eliminate an unnecessary move, he then secretly raises the two cards to beneath the second pair of Queens as they are brought over the pack, so it never seems as if these cards even so much as touch the packet beneath them — and they never do! Thus the transposition occurs under the cleanest and most mystifying of conditions, as does the instant vanish of the signed selection, using the same finessed add-on.

Howard Schwarzman's "Night Visitor" is, in my estimation, a lesson, and a laboratory example, of sophisticated sleight-of-hand magic, representing an exquisite synthesis of analysis, construction, method, technique, and effect. Indeed, I have on occasion utilized this trick as the basis of a workshop in the kind of methods and handling it relies upon. It is a great piece of magic, a great lesson, and comprised a profound lesson for me when Howie first taught it to me. We returned to discussing it many times over the years, and I always expressed my appreciation the treasures it contained and the lessons it conveyed.

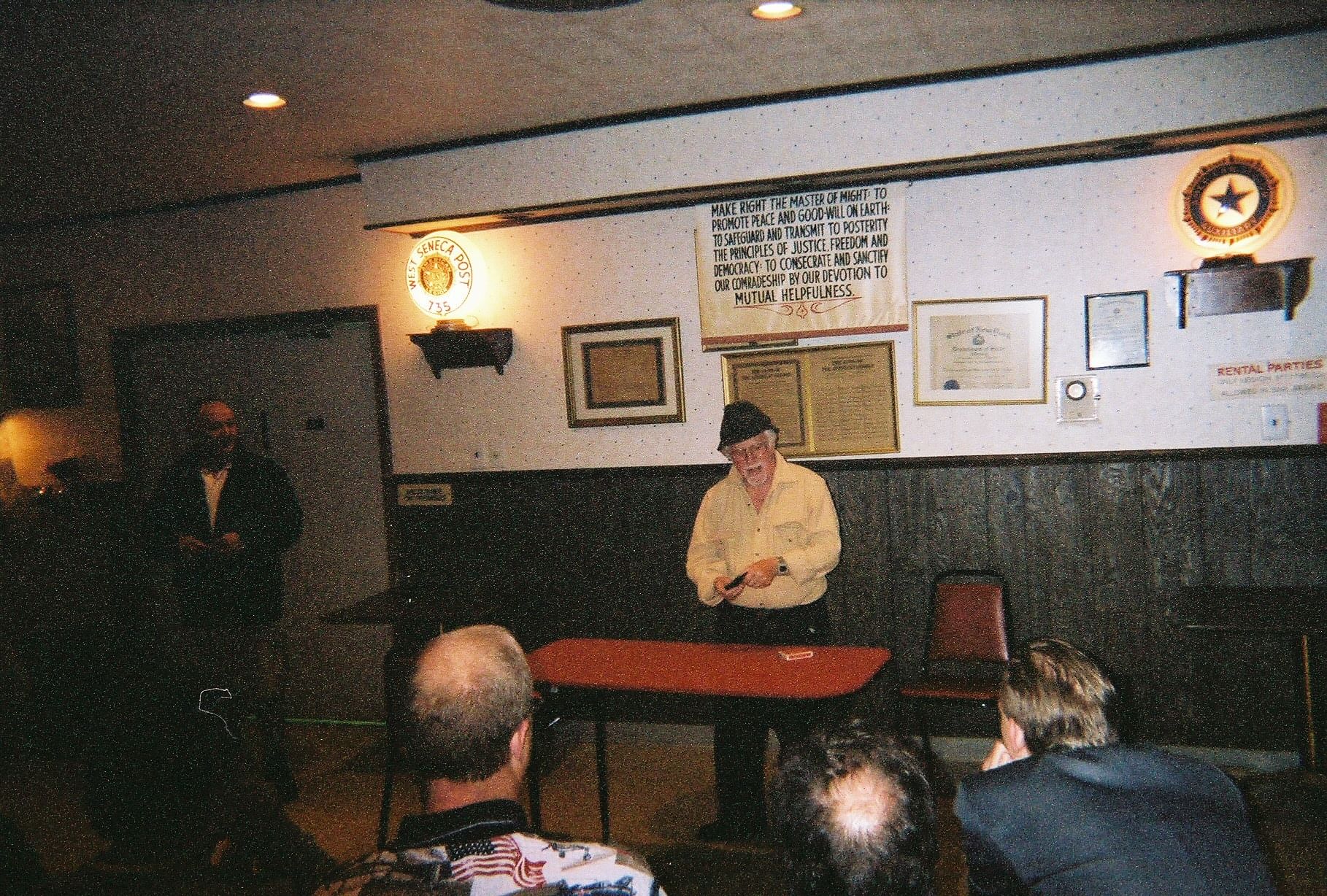

Howie at the 4F Convention. Photo by Dale Ferris

Howie at the 4F Convention. Photo by Dale Ferris

Recently, Gary Plants posted a rare video on social media of Howie performing Ramsay's Three Coins in the Hat, shot back in the 80s at the CEMK convention. This spontaneously triggered a thread of accolades and appreciations for Howie (to which I contributed). Most of us hadn't been in touch with Howie for years, but knew that for some time that he had been in a nursing home, suffering a sadly progressive decline due to Alzheimer's disease.

Then, suddenly, coincidentally, just a couple or three days later, someone discovered that Howie had passed away the previous month. I am sure all of us felt even more saddened that this lovely chain of tributes had spontaneously arisen, and Howie would never see them.

In the face of this news, I have two more stories to offer. One, some will doubtless insist, might appear unflattering to Howie. But I don't really think so — especially in the particular version I have to recount, even though it's a story that has often been told before, and by many. While all of us who offered our public appreciations of Howie, on the video's comment thread, emphasized his kindness and generosity with knowledge, as well as his prodigious skills, none of us, doubtless out of respect, ventured to comment on Howie's renown as a loudmouth. But I'm going to tell one story about that streak in Howie's personality, because he, and history, deserves a more complete story. It's inappropriate to let Howie Schwarzman go down in history as a sweet, gentle little guy. He could be a fine gentleman, surely. But he was also more than that, and notoriously so.

In Vernon's later years, while in his late 80s and early 90s, I performed regularly at the Magic Castle. We would always spend nights together talking in his reserved seat, just outside the Close-up Gallery, and I would sometimes join the late night crowd heading off to a two a.m. diner breakfast upon the Castle's closing, sitting with Vernon and cracking jokes and listening to him tell tales that weren't always just about magic, and weren't always readily repeatable.

During one of those visits, I walked into the Castle early on a Monday evening, the first night of my performing week, and Vernon immediately greeted me from his seat. I sat down next to him. "New York! But you're still in Maryland, now, right?" I confirmed that he was correct. "Let's see, who else is from around there? Howard Schwarzman is from Baltimore." "Yes, that's right, he is." "I'll tell you a story about Howard. You know who Eddie Tullock is, right?"

Howard performing at the 4F convention (photo by Dale Ferris)

Howard performing at the 4F convention (photo by Dale Ferris)

Now, the moment the Professor mentioned Eddie Tullock in the same sentence as Howie Schwarzman, I instantly knew the exact story that Vernon was about to tell me. It was a popular back room tale about Howie, and I had heard it, on multiple occasions from multiple sources, and even repeated it. But I was not about to say any of that in the moment. What fool would open his mouth about such a thing, only to be denied hearing the tale out of Vernon's own mouth?

So I simply acknowledged that I knew who Tullock was, and let the Professor continue.

You need to know, if you don't already, who and what Eddie Tullock was. Eddie Tullock was the founder of tradeshow close-up magic. (Other early tradeshow workers in the Sixties included the likes of Karrel Fox, but they were doing platform performance.) Tullock created and codified a format for close-up magic at trade shows that is still in use today — namely the raised table positioned at the aisle, with the magician behind it standing on a slightly raised base, performing close-up magic and integrating the presentation with the client's marketing and branding content. Tullock was enormously successful, as were many others in his immediate circle and who then came in his wake, many of whom were booked by Tullock's agent, who made Tullock and many others a great deal of money in the Sixties, Seventies and beyond.

Tullock was incredibly successful because he was incredibly effective. He was entertaining, sociable, and communicated the client's message in a palatable form that delighted and engaged the audience. He was a fine close-up magician but he was not a finessed one. In many ways he came from a similar school as the early Chicago Magic Bar workers, exemplified by Matt Schulien — "A Force and a Steal!" was all you needed, along with the ability to palm a card, and do a Top Change that might register on the Richter Scale but still managed to be invisible thanks to expert performing, misdirection, and management skills.

As the story went, one day Howie Schwarzman managed to get into a trade show to watch the veteran and masterful Tullock working the crowd. Upon Tullock's completing a set, and as the big crowd dispersed, Howie made his way directly to the front. "Here, Eddie, let me show you the right way to do that Top Change ..."

Now, this story, which I had heard previously, would always get a laugh from anyone who knew Howie, because it was a perfectly hilarious example of his sometime social cluelessness and his inescapable obnoxious streak. Of course Howie's Top Change was more refined than Tullock's, but the idea of correcting this past master, much less on the job, was so deeply clueless as to be almost inexplicable — unless of course you were Howie Schwarzman, who would then probably wonder why in the world anyone would laugh at it.

But what I remember, and most love, about Vernon repeating this tale to me, was his appreciative and wondrous and affectionate postscript.

"So Howie walks up to Eddie Tullock and says, 'Here, Eddie, let me show you how to do that Top Change ... !' Can you imagine that? Eddie Tullock!" And Vernon laughed heartily. And then, exhaling, he said, "Howie's such an asshole!" And laughed again.

I could have died laughing myself. I didn't tell the Professor that I had heard the story before. But here's what's wonderful about this story. It was widely told not because its subject had perpetrated some great crime, but rather because it illuminated an inescapable, undeniable aspect of Howie's personality that we all knew, and tolerated. And when Vernon said it to me, there was not the slightest hint of meanness, or darkness, or even judgment in the comment. He laughed when he said it, and there was, in that laugh, appreciation and affection and wonder at the personality that Vernon had known, and indeed helped raise as a magician, for decades. And I tell it now, I hope, with that same sense of laughter, and appreciation, and affection, and even wonder — and I hope the reader will take all of those elements from it, because that is entirely how it is intended.

I can’t leave a story about Howie that involves the Top Change without mentioning that Howie taught me the most important rule for the misdirection that accompanies the Top Change, namely that you must always first move one hand, then the other hand – it doesn’t matter which one, it can be the card hand then the deck hand, or even the other way around – but you must never move both hands at once.

But in teaching this lesson, Howie would invariably then demonstrate his original exception that tests the rule. “Except for the Jewish Top Change,” he’d say, and then he’d demonstrate as follows. Holding a card in one hand and the deck in the other, he now moved both hands together, executing the exchange but completing the action in a gesture of hunching his shoulders upward in a puzzled physical and verbal exclamation: “Who knew?”

In the early 2000s, I produced a series of intensive three-day seminars on sleight-of-hand magic called Card Clinic (there was also Close-up Clinic and Stack Clinic). I would bring in another presenter to share the teaching content — Roberto Giobbi taught the Card Clinics with me — and among other elements, I would always present a surprise mystery lecturer on Saturday afternoons, immediately following lunch. I worked hard to keep those identities a secret. The Clinics were held at various locations all around the country, and each featured a different mystery guest. The inaugural Clinic, in New York City, presented Herb Zarrow. Other mystery lecturers included Harry Riser and Johnny Thompson, among others.

All too often when I think back about the lessons I learned from my many teachers and mentors, I must accept that I never had the chance to say thank-you. By the time I decided to become a professional magician, Lou Tannen was gone. I pay tribute in my work, and in my writing, and always try to pay it forward — from Lou, and so many other generous and influential guides.

When I produced my fourth Card Clinic in Washington, D.C. in 2005, I knew well in advance that my mystery guest lecturer would be Howie Schwarzman. I invited him, I wined and dined him, I introduced him, and I watched with delight as he repeatedly fried my attendees, and opened their eyes to beautiful and stunning sleight of hand. It was a small, but distinctly intentional, way of honoring him, and of saying thanks. And I think Howie knew it, and appreciated it. (And maybe it's why he didn't heckle me much at Denny's.)

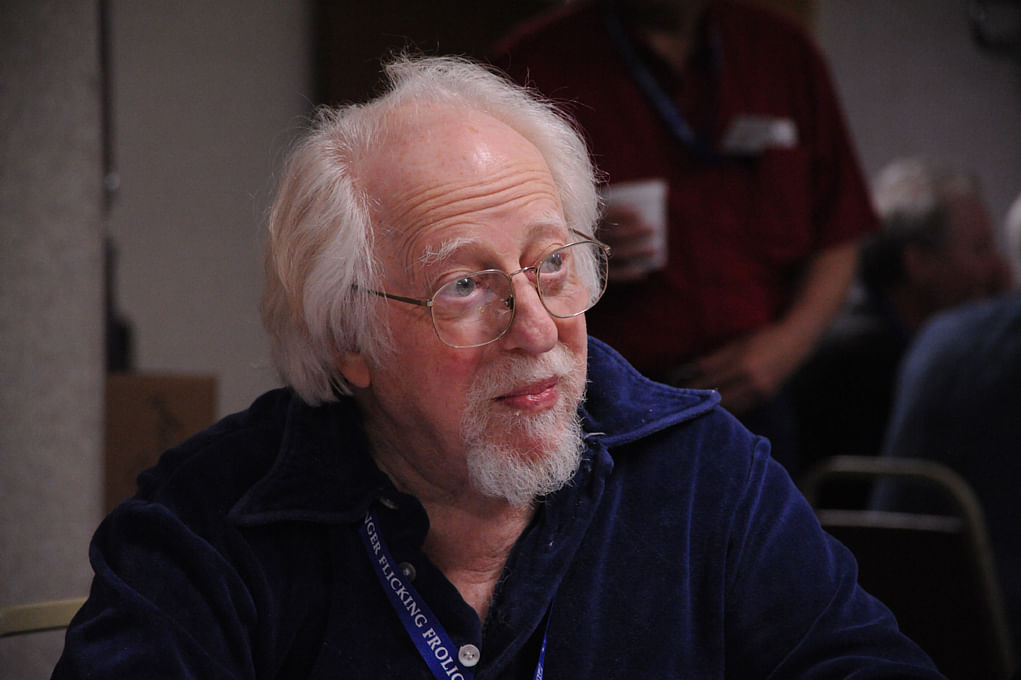

Photo by Dale Ferris

Photo by Dale Ferris

I've had the pleasure of knowing a number of masters of the Classic Pass and its variants. I've known Derek Dingle, Ken Krenzel and Howie Schwarzman on the East Coast, and other Pass masters on the West Coast, including Earl Nelson, Larry Jennings, Bruce Cervon. And I knew Geoff Latta intimately, who taught the Pass to me.

But Howie's approach to the Pass was distinctive. Of course like most Pass Masters he knew many and did many expertly. Besides the aforementioned and rarely seen SWE Shift, he was also the finest exemplar of the LePaul Spread Pass of his era.

Howie also revealed to me the true answer to the age-old question: When do you do the Pass? Howie's answer — the answer — is this: "It depends on how well you do it." That's the real answer, without irony. To elaborate: If you do the move well, you do the move instantly, immediately upon the return of the selection. But if you don't do it well enough for that timing, then you wait, and misdirect more heavily, seizing attention away from the pack, and then execute the Pass a bit after the delay. Perhaps the missing but implied important element in Howie's answer is this: Know thyself.

Howie didn't like shifts with moving misdirective covers, like riffles or dribbles or jiggles. He didn't like any of that, and didn't believe in it. Howie was a purist. His favorite shift was the Classic Pass, done perfectly still, with no covering action. And despite the fact that he had very small hands, this shift, in his hands, was virtually invisible. There was truly nothing to see. There was no detectable movement. It was utterly fast, totally silent, and completely still. It was, in essence, perfect — or certainly as close to perfect as is humanly achievable. This is the simple truth of it, as anyone who knew Howie and witnessed it will attest and confirm.

Often, when demonstrating the shift for a newly acquainted magician, Howie would say, and do, the following. Which, I believe, perfectly captures everything I have tried to tell you in these pages of tribute to one of my teachers.

Howie: "Have you ever seen the Wish Trick?"

Magician: "No."

Howie might have that magician take a card and return it, or instead simply spread the deck, turning over a random card somewhere in the midst, enabling the face to be visually noted, with no commentary or instruction necessary. Let's say he tips the card over, face-up in the spread — let's call it the Nine of Hearts — and then tips it over again, face down, and closes the spread. That's it. That's all there is to see.

After a pause, he simply turns over the top card of the pack. It is now the Nine of Hearts.

Howie looks up at the face before him — the now widened eyes, the slightly slackened jaw.

Howie: "Don't you wish you could do that?"

Yes, Howie, I still do wish I could. But as it turns out, you helped a kid fulfill an even greater wish: to become a magician. Thanks for the lessons.

Howard Schwarzman performs John Ramsay's "Three Coins in the Hat." Video courtesy of Gary Plants

Thank-you to Brian W. Morton and Gary Plants for providing a number of the accompanying photographs. The Morton photos come from Steve Friedberg's collection.

Back to blog homepage

Similar posts on the blog: