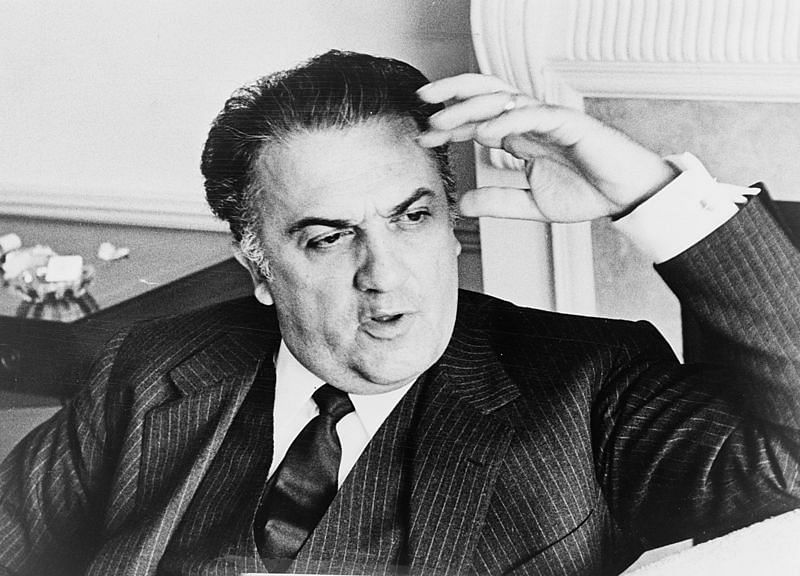

All art is autobiographical.

By Eric Richardson - Wednesday, March 25, 2020

The famous Italian film director's quote stoically greeted me every time I entered my high school art class. It was mounted on the wall above a supply table and was just one of over one hundred quotes I encountered daily. One time I did actually try to count every quote I encountered in one day of classes and the total was a staggering 159! They were sticky-tacked to doors, taped to windows and thumb-tacked to bulletin boards in almost every classroom I entered. There were pithy quotes from philosophers, mathematicians, authors, presidents, famous actors, dead rock-stars and an even an anonymous cat, hanging from a tree branch, with the sage advice to "Hang in there." I chalked up this strange quote-fetish to a bizarre psychosis universally shared by all teachers. Over the years, the parade of platitude producing pundits came and went in a blur, but I never forgot Fellini's quote. It haunted me. As the years went by, Fellini's words would float through my mind, a faint and ghostly whisper. I would let it drift away again with only a vague sense that his declaration should mean more to me than it did. It remained an enigma.

It was not until I was simultaneously studying art history and philosophy at university that I began to get a sense of Fellini's observation. As I encountered the life and works of some of the most renowned artists, the connections between their artistic expressions and their world views started to become clearer. I began to see how artists like Picasso, Warhol, Monet, Gauguin, John Cage and so many others had revealed important things about themselves through their art. The connections were undeniable. Appreciating art (and the artists behind those works) took on a new and exciting dimension.

Yet, while I found all of that fascinating, I didn't apply it in any way to magic and especially to my magic. I believe the main reason for this was that I simply didn't view magic as an art form. Perhaps this was inevitable since, years earlier, my beginning exposure to learning and performing magic was full of dismal throw away "patter" lines and bad examples of insulting spectators for a laugh. Certainly, none of that encouraged me to view magic as anything but a collection of methods and gimmicks created for the singular goal of fooling people (and maybe making them laugh). And it was even harder for me to see beyond all of these trivial, hollow and un-artistic presentations when they were being reinforced by the magic I typically witnessed. (This was pre-internet...) For instance, my introduction to sponge ball magic, as a teenager, was a fifty-something year old magician making a sponge-penis appear in my hand for the..."climax" of the routine. Yeah, that still creeps me out.

So, perhaps it is understandable that I struggled to see that there could be a different path—that magic could be art. It wasn't until I stumbled upon a small booklet by Eugene Burger that I began to encounter a different vision for what magic could be.1 Here was a magician who was talking about respecting himself, his work and his audiences. He was discussing important things, asking deep questions and taking his magic seriously. And he had the audacity to expect his audience to take him and his magic seriously as well. This, for me, was a paradigm shift; an epiphany. Eugene approached his magic as an artist. I was drawn to this and even though I began to see magic as an art, Fellini's words continued to lie dormant, waiting for the right time.

- O -

A few years later, on a long walk in a forest (a favorite pastime of mine) Fellini's words visited me again. "All art is autobiographical." Really? Out of curiosity, as simply a mental exercise, I decided to test those words on a magician. I decided to apply my little test to Eugene and his magic (at that time I was more familiar with his magic than that of any other magician). Could I know anything about him as a person as I considered his published presentations and choice of effects? Did he reveal anything substantial about himself in his performances and even his choice of dress and props? The answer, of course, was yes! I quickly made a mental list, being careful to only add things to it that were based on his presentations—not on other biographical information I had learned from his other writings. As I surveyed what I knew of his body of work, I realized I knew some very real things about him. His art was autobiographical on a deep level. I knew something of his personality, sense of humor, interests, passions, opinions and worldview. At least for him, Fellini's words seemed to ring true.

Surprised and encouraged, I chose to press the matter further as I walked deeper into the forest. Did Fellini's declaration apply to every magician? I laughed out loud, sending a startled bird heavenward, as I decided to apply the test to that sponge-penis wielding wizard from so long ago. Would it apply to him? I thought back on the several performances of his that I had witnessed. To my amazement I had to admit that his performances did, indeed, tell me some things about him. His performances were autobiographical as well, but they told a very different "story" than Eugene's.

As I compared and contrasted my two examples, I had to conclude that Fellini was correct. And not just for painters, sculptors, composers, filmmakers, etc. But also for magicians—and it was equally true for the Burgers and the bozos. And as I continued walking down that forest path, I soberly and reluctantly acknowledged that my magic was, therefore, autobiographical as well. My magic—all of it. And this was true whether I recognized it and embraced it or not. It was an inevitability. A universal.

The crescendo of these rapid-fire realizations stopped me dead in my tracks. I admit I was unnerved, apprehensive and intimidated by this revelation. I stood there, quiet and motionless, for a long time. I closed my eyes and listened to the sounds of the forest around me and wondered how I should respond to these revelations. The way forward was not nearly as obvious as the clearly marked forest path I was walking down. It took absolutely no courage to proceed down a path already carved and so nicely maintained. But I realized that I'd have to carve my own path through a very different kind of forest. Sometimes it was even a dark and scary place. It would take courage. I realized that moving forward in the art of magic meant coming to a real understanding of myself. A studied, intentional understanding. It was time to ask a question no one else could answer for me: Who am I? Not in a general self-aware sense. I had a good grasp of who I was in general. No, I realized that I needed a deeper analytical understanding of who I was. A conscious and thoughtful understanding—knowledge that I could intentionally use as I pursued real artistic expression. And then, if I could answer that, a second question lurked in the shadows: exactly how much of myself do I want others to see during my performances?

"My desire to view magic as an art form and to be an artist, whose medium was mystery, triumphed over my fears and apprehension."

I determined then and there that my desire to approach magic as an art form and to be an artist, whose medium was mystery, triumphed over my fears and apprehension. I would carve the path by putting in the hard work and find my answers. Bold thoughts! However, for months after making that promise I procrastinated, afraid that I would not really be able to find the answers I sought. Finally after attending a Mystery School (in the mid-1990's) run by Jeff McBride, Eugene and others, I was inspired to sit down in my college dorm room with a pad of paper and do my best to try and fulfill the promise I had made to myself—no matter how long it took.

- O -

As it turned out, answering the question of who I am didn't require a visit to a mysterious monastery on a mountain or some unique talent or skill. There was nothing mysterious about it. It was simply asking a series of questions and being honest about the answers. Asking questions about what I like and don't like, what I value and why, what my interests and hobbies are, etc. Creating these lists allowed me to begin to really take an inventory of who I am. Doing this took some courage, as I said, since some of the answers were not really who I ultimately wanted to be in magic or in life. I had to decide to change some things to be a better artist and a better me.

When I finished this exercise I felt very secure in my deeper understanding of who I was and it was a very liberating process. Recently, I have returned to this exercise, sensing that this self-inventory needed to be repeated since I realized that as a result of going through some major, traumatic and life changing events, I had changed as a person in many ways. I am not the same person I was even five years ago and it will affect my art. I imagine that I will need to return to this exercise occasionally since I will continue to change over time and I want to be conscious about how these changes are reflected in my art and have a thoughtful control over that process.

The second question, "How much of myself do I want to reveal in my performances?," is a fascinating one. It is a question that I am constantly exploring. How much to reveal? How deep does one go? When and how does one do so? What do I not wan't to reveal about myself?

"Audiences appreciate the benefits of revealing more of who you are in your

and are more likely to connect with performers who enable them to see themselves and their world in new ways."

Ultimately, I think each performer has to answer these questions personally and the answers will be different for each individual depending on many variables. Some performers reveal very little about themselves in the course of a performance or even a career. I respect that choice—assuming it is a conscious choice. But, I believe there are good reasons to seek to reveal more about yourself than just the bare minimum.

I won't make a full analysis here of what I believe to be performances, but I will list what I think are the most important ones to aid your own exploration: connection, texture, integrity, artistry and message. If you take some time to thoughtfully explore each of these, I am sure you will see how revealing more about yourself, in at least some of your performance pieces, can aid you in creating amazing performances. Allow me to briefly illustrate by highlighting one of these benefits: connection. I believe that audiences appreciate, and are

more likely to connect with, performers who enable them to see themselves and their world in new ways. I believe this happens primarily in the sharing of yourself and your uniqueness as a person during your performances. Intentionally harnessing the power inherent in the autobiographical nature of your performances will allow deep connections between you and your audiences to form that will make you (and your magic) memorable, unique and meaningful to them.

I have come to not only accept Fellini's words as true, but embrace them as part of my path of magic. I constantly try to remember them as I create my presentations because if I am creating art, then it is autobiographical. I am saying something about myself, what I believe, how I view the world and what I care about in every performance. So what do I really want to say through my art? What kinds of things do I want to communicate or reveal? Answering these questions changes how I approach my magic, my scripting and my interactions with my audiences.

How do you reveal more about yourself in your performances?

1 It was Secrets and Mysteries of the Close-Up Entertainer. Intimate Power and The Craft of Magic followed soon after. It is not an overstatement to say these three books changed my life in significant ways.

Back to blog homepage

Similar posts on the blog: