Wayne's World

By Bob Gill - Tuesday, December 5, 2023

It all started when we first bumped into one another at Ken Brooke's Magic Place in Wardour Street in the early part of the decade taste forgot, the 1970's.

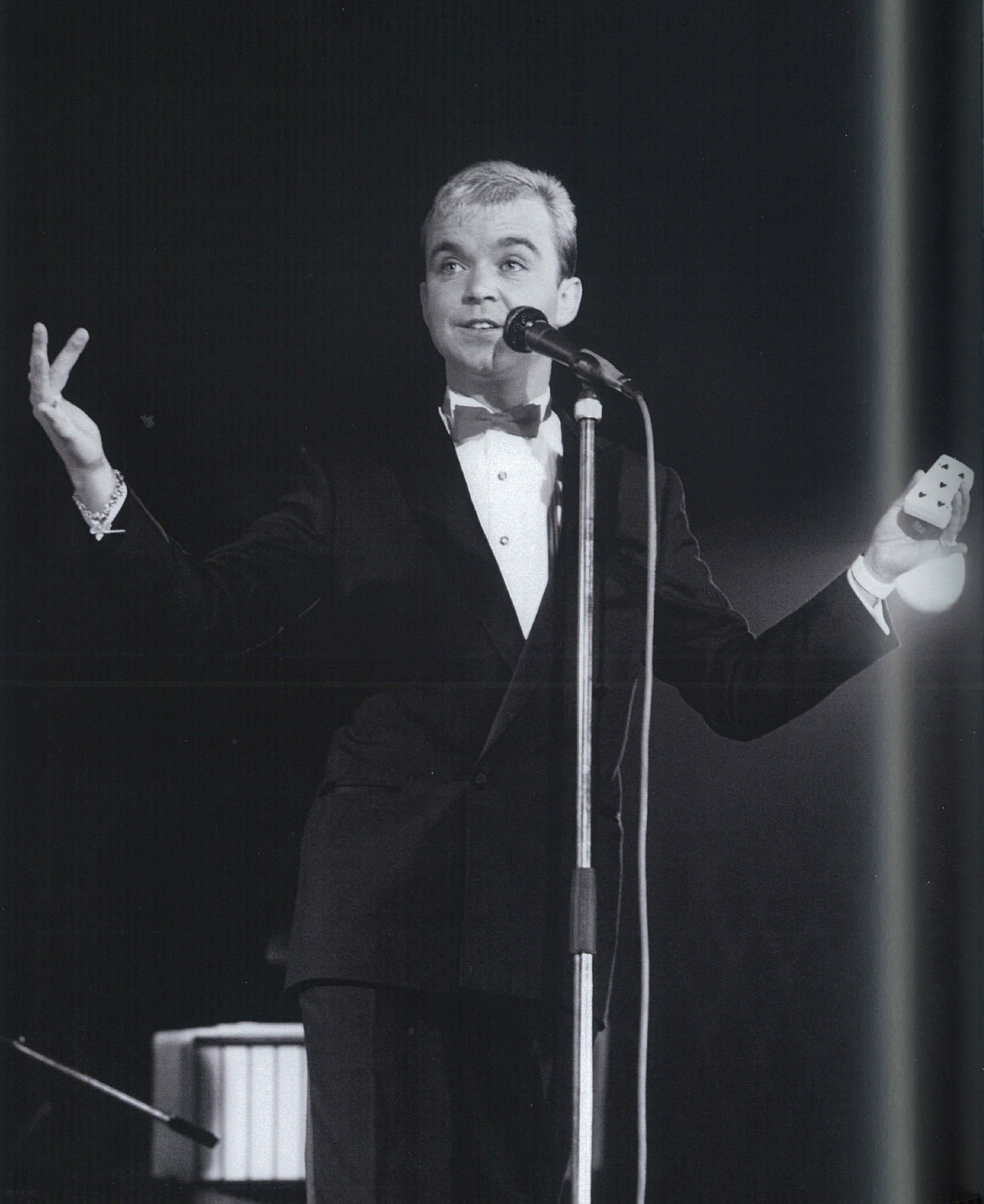

I was 5 years older than Wayne (indeed, I find I still am) which is a yawning gulf in time when you're twenty. Not long afterwards I saw Wayne in action onstage at the annual IBM British Ring Picnic, when Roy Johnson introduced this character he had been mentoring, who looked about fourteen but proceeded to perform in the stage show. What the young Wayne performed was pretty standard fare - prop tricks fashionable at that time - but it wasn't what he did so much as the way he did them. The promise he showed was rooted in his stage persona - how he carried himself, a beguiling mixture of charm, underpinned by the swagger of youth. We all duly marked him down as One To Watch. This was borne out the following year when he won the IBM close-up competition, the Zina Bennett Cup (the year after I did, which further bonded us). A few months later I lectured at the Leicester Society, staying with Roy and his wife Janet, and Wayne came over for a session.

We went on to follow parallel paths, working in the clubs with the light comedy magic that had become popular thanks to the likes of Paul Daniels. During that time I had the pleasure - with more than a hint of envy - of watching him grow from a precocious, twinkly-eyed teen into a seasoned pro and then to go on to become a master of his craft. Although performers are inherently competitive, it was with no hint of malice I observed him rapidly outranking all of his contemporaries; it was obvious to all of us from the get-go that Dobbo was destined for greater things.

He quit his factory job aged 21 to turn pro, egged on by several people whose advice he valued telling him he had what it took. He caught the eye of an agent who booked this raw youngster into tours of punishing clubs in Scotland and the North East, which had the reputation of eating their own young. Travelling around in his beaten-up Datsun, which often doubled as his bedroom for the night, he showed the resilient and resourceful attributes that would later serve him so well when he made it. His ability and drive to watch, listen, learn and apply that learning, together with his acute instincts for anything related to engaging an audience, marked him out. He gradually stopped dying and won them over, until he began to get encores as a matter of course. It was at this early point in his career that he first made the stumbling beginning of his signature Voices bit.

His appetite for work was voracious; he'd cheerfully take on three or even four gigs in a day. Working with major variety acts of the time, it was only a matter of time before he caught the eye of manager Leon Fisk (who also happened to manage Freddie Starr). He gained enormously from his two seasons opening for the mischievous Freddie Starr in this country, with whom he toured and guested for on TV for three years, and Englebert Humperdink, for whom he opened in Vegas for two years. Those five years honed his performing chops, polished his onstage presence and turned him into a rounded, world-class comedy magical entertainer.

At this juncture he was presented with a happy if wrenching choice: front his own Vegas show, or his own ITV series. At the same time he was booked to perform before the Queen at the Royal Variety Command Performance, in 1989, when he proceeded to steal the show with two 50p sponge balls and his by now Voices bit honed to a sparkling crowd-pleaser. Finding Vegas a little shallow and something of a hamster wheel, he and his assistant wife Karen choose to return to Blighty.

His television series regularly attracted 11 million viewers thanks to his producer/director Nigel Lythgoe giving him space to build his onscreen presence. He always made sure he surrounded himself with quality; Linda Lusardi as his assistant, Pat Page his magic advisor, Russ Stevens his illusion advisor, Charlie Adams his co-writer. In the Legacy we track how those three series unfolded, and detail every routine. He was always alive to what was current; at the height of Wayne's onscreen fame Paul Daniels was entering his twilight TV years: Mister BBC with its old-school feel. Wayne's whole approach was young, cool and contemporary, with a modern studio set, illusions that looked like they'd been built for a sci-fi film, a page three girl for an assistant and a theme song by Queen. This certainly got to Mr Daniels, who proceeded to wage something of a feud with the young pretender in the magic press and the tabloids.

All magicians trade in secrets; unknown to everyone his biggest was mind-blowing. At the same time as learning he'd bagged that Royal Variety Performance, a troublesome pain in his leg caused him to consult a specialist, who told him he suspected he'd contracted Multiple Sclerosis. It was not a definitive diagnosis: he'd have to wait three years to get that. So the entire decade at the apex of his career -- Royal Variety shows, three television series, a full evening illusion show that toured the UK for several years, the darling of the lucrative corporate appearance circuit -- was delivered whilst his medical condition hung over him, intruding further into his life, robbing him of the use of his legs, then one hand, followed by the other, until his paralysis confined him to a wheelchair. Having fought his way to the heights of stardom, he took on another fight: the lengthy, cruel and debilitating grind downwards to almost complete dependence.

It also saw the dwindling of his considerable earnings, his savings, and both his marriages. His second marriage was marred by the abuse he suffered at the hands of his spouse, which left him feeling vulnerable and frightened. Yet like all of those who knew him I was blissfully unaware of the dysfunction of his second marriage and the abuse he was withstanding and concealing, partly from shame, partly from fear of being confined to a nursing home where he'd lose his sense of freedom.

Faced with the reality of his financial position he needed to earn a living. As a quadriplegic this was always going to be a challenge, until he hit on the idea of following in the footsteps of his hero Ken Brooke and market his own creations as a magic dealer. DTrik was born, which he ran more or less single-handedly until he met his business partner, Mike Sullivan, who took on the heavy lifting of running the business, leaving Wayne free to sit and dream up magic tricks, a feat he seems to be able to pull off at will. In the process he virtually invented a new artform: the hands-off routine.

We stayed in touch throughout the years following his enforced retirement from performing, and he was always great company. He's a great teller of jokes, with a seemingly endless supply of pro gags: the sort of off-the-wall stories of dubious taste pros love to swap backstage. Now his condition is such that when he laughs it quickly turns to wheezing and spluttering. When he's really tickled by something, he'll appear to virtual drown in spittle and gasp for breath. On one occasion I got close to calling an ambulance. He loved every second of it - but nowhere near as much as I did.

This sense of fun is characteristic of how Wayne is with his friends, and is one reason he is invariably surrounded with magic and showbiz mates whenever he goes to a function, or they assemble at his place. His greatest joy is to be amongst a crowd who are bantering and laughing - he is invariably the one laughing the most. Generally he'll wait until the biggest laugh dies down, then unleash his sole contribution to the session - and sly old pro that he is, he invariably tops what's gone before.

I was brought back into the Dobson orbit five years ago, when he in turn complimented and delighted me with an invitation to participate in some writing and performing projects he had in mind. He had decided he preferred written instructions to the films that had become the norm amongst contemporary dealers and whose tendency to hype he detested. So I was also drafted in to write found myself brainstorming then writing up his creations for DTrik and Alan Wong, little realising at that point how insanely productive they both were.

One thing that greases the wheels of his working relationship with those of us close to him is the recognition that we are interdependent: our exchanges and need for each other's attributes flow both ways. The standards he expects of you are as high as those he inflicts upon himself. Live up to that and he meets and treats you as an equal, which is very gracious (and smart) of him. Fall below it and it frustrates him beyond belief.

Frustration is a condition he has had to learn to cope with, since his reliance upon others for many aspects of his daily existence inevitably puts pressure on him to bite his tongue. Because he is dependent on us to put his prolific ideas into practice and follow his direction he becomes quickly bewitched by the idea and cannot wait to make it a reality. Of course, occasionally real life intrudes, and one is not always able to be at his beck and call the instant he comes up with an idea. This is what frustrates him the most; he is well aware of the limitations of how far he can take an idea, and is impatient for someone he trusts to intercede and help him bring it to fruition. To own such a creative, highly active brain within the body of a quadriplegic is at once continually frustrating and restrictive.

His condition is such that strict routine becomes not just important, but a matter of survival. Modern telecommunications are lifesavers for Wayne, who avidly makes the most of the access they offer him through his voice-controlled headset. For much of his waking day though Wayne inhabits a solitary world. Although he has daily carers and regular visitors, there are extended periods of his day when he is alone: partly by choice, because this becomes his thinking time. Being paralysed from the neck down, everything Wayne has control of resides inside his brain. In losing so many of his sensory powers, it becomes clear that he has compensated by how he uses his brainpower. This manifests itself particularly in his acute powers of memory and visualisation, coupled with a forensic attention to detail that never fails to impress me. As you'll be aware, inventing a magic trick is a serial act of creativity: you come up with an initial idea; you generate a way to make it possible; you by the props, pick them up, and practice handling them, gradually over time honing it through physical rehearsal.

Wayne has to forego most of these essential steps in the process of bringing a magical effect to life; he does that is by brainstorming the routine with someone who has their own brand of creativity and experience to offer. This collaborative process is vital because it removes the solitary nature of his existence; it allows him to bounce ideas off others whose abilities he values, so as a result the trick is enhanced in the process. It gives him the opportunity to get any special apparatus made, and for a pair of hands to replace his and to practice it on his behalf; it validates the idea, or causes him to reject it: he is not afraid to ditch what many others would be happy to have invented, if it falls short of what he has in his imagination.

It is always a pleasure, never a chore, because you know two things are about to happen when you receive a call from Wayne Dobson: there's the beginning of a fine idea about to be unveiled, which you are privileged to have first sight of. And you are going to laugh long and loud and have a great time in the process: the hours fly by.

When I brainstorm ideas with Wayne, I'm always aware that he has forgotten more than most of us know about magic effects, techniques, and principles. This man lives magic 24/7. We'll pass ideas to and fro; when we're happy with it I'll go away and write the instructions to the effect, or Mike will shoot an illustrative film. Then it's over to Mike to get the apparatus manufactured before marketing, selling and delivering the product to their customers.

You can imagine that deconstructing, say, a trick with a pack of cards can get quite complex. When an able-bodied performer is practising, they can check their progress throughout; Wayne has none of this available to him, he can only carry a mental image of the entire sequence of actions. But he will patiently explain to tell me in blistering detail:

"You shouldn't deal the third card onto the left-hand pile. You need to do another double undercut first, then you can hand the deck to the spectator to deal onto the right-hand pile. When he has dealt the fifth card - no, sorry, the eighth card; the fifth ends up getting lost in the bottom half of the deck later when you complete phase 2..." All from within his memory.

At the same time, he sought someone to help him complete an idea he'd been pursuing for a decade: knocking into shape the assembly of bitty anecdotal reminiscences of his life, which took up all of three dozen pages, most of which had already been published in his earlier books. Working hand-in-hand together we turned that handful of reminiscences into nigh-on 400 pages during the four years or so I spent working with him. We settled into a routine, speaking most days for a couple of hours on Skype or at his apartment in Surrey, and I effectively interviewed him, teasing the memories and the forgotten events and anecdotes out of him. A significant benefit of the process was that reliving his life story prompted many events and anecdotes, which have made the book all the richer. It could easily have run to another hundred pages or more.

Our challenge with his life story was that we were largely reliant upon his memory. He'd offloaded most of his extensive collection of memorabilia, props, illusions, because he is unable to even reach out and touch them. So I became his researcher too. I had a ball over many months talking with the panoply of people involved in making him a star -- programme makers, performers, stars, advisors and an army of luminaries from the magic world. It turned out dropping the Dobson name opened otherwise impenetrable doors, and all of these names fell over themselves to remember stories, and express their huge admiration for what a star he was as a performer, and what an inspiration he became once life hurled its worst in his direction.

I would write up what we'd discussed, send him the pdf, which he would read onscreen. Then we'd go over it together, me reading the text aloud to him, correcting any anomalies and adding any additional stories the text prompted in him, sparked by the procedure we went through. It might sound laborious, but bear in mind I'd become trusted with such deep and brutally honest insight into the thinking of one of my magical heroes, and his life so well lived; I was having a ball.

Perhaps the biggest compliment I can pay Wayne is that after just a few weeks I came to forget the fact that he is disabled. In that, I believe, lies his ultimate triumph over the curse of Chronic Cerebrospinal Venous Insufficiency (MS to you and me).

It's instructive how brutally honest he can be about himself and what drives him: Wayne does not kid himself. Add to this a remarkable resilience, and strength of spirit, and you can see within him three of the crucial behaviours that underpin success: abiding self-belief, a refusal to accept failure, and an unrelenting drive to achieve more.

I actually wrote his life story four times. It started as a project dreamt up by his lovely, smart manager Mary Fisk, who had interested Mirror Publications in a book on Wayne's life for the public. There was also talk of a documentary, and some sketchy ideas for a sitcom. So after 18 months of toing and froing with Wayne, I produced a first draft that we were both happy with. The publishers and his management felt it was not sensational enough - they wanted more juice about his eventful second marriage. It is a discouraging fact that victims of abuse quail at speaking out in public; when these victims are not only male, but also disabled, it adds additional piquancy to Wayne's fortitude in being so revealing. The abuse he suffered at the hands of the person closest to him at the time has undoubtedly left a deep mark on Wayne's psyche, but he is still able to discuss it stoically.

So off I went and rewrote the manuscript, with four whole chapters going through the ups and downs of those ten years. Publishers and management were happier, as was Wayne, since he had doubtless found the process of unburdening himself in such a raw manner therapeutic. But I couldn't shake feeling a trifle -- well, grubby. This was compounded when I showed it to a few magicians whose opinions I value, who felt it was far too personal and sensationalist. Wayne agreed to toning it down more than somewhat, so off I went and rewrote the text. But now we had neither one thing nor the other, satisfying no one. Then the worst came to us out of left field, when Mary was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer and passed on within a matter of weeks. Wayne was devastated: Mary had always been like a showbiz mum to him, and he was still smarting from the loss of his real Mum. With Mary went the link to the Mirror, and the project stuttered.

I'd harboured the idea of turning it into a two-volume set aimed four-square at magicians, one volume his life story (tailored yet again), the other the routines he'd made his career with. This in turn begat the three volumes it finally yielded: the life story, his TV and stage routines, and new material he had intended for a fourth television series before ITV callously dropped him out of fear of the public reaction to his worsening medical condition.

So now the two of us worked intently through his various routines for another year or so. In all the work we collaborated on, Wayne approached the effect as a performer, describing how he would perform it, despite being unable to do the effect he was explaining selling to others. Wayne was standing apart from his original performances and critiquing them, rather like an objective director, and over the years has continued to develop them as if he were still performing them.

Having said all that, imagine the demands on him to bring these books to fruition. As they went through the many changes they had to during their gestation, Wayne had to keep track of sections across different pages and chapters, once more bringing his elephantine memory to bear. Once again I felt so privileged, to be learning his best work from a master of our craft. Mind you, he was not always easy work. One day I tentatively suggested we discuss his signature comedy bit -- perhaps the finest comic magic device of our time -- the Voices. If you don't know what I'm talking about, look up his Royal Variety Performance on YouTube for a masterclass from someone at the top of his game. His reply was, "But I just did it, working it out over several years of gigging." A short chapter, then. Over several weeks I doggedly worked on him, until we had a couple of dozen pages examining the bit in forensic detail, and it's perhaps the standout of the trilogy for me, possibly because it was so hard to pin down and explain, mostly because it is such an iconic bit.

Confident in the material, I approached Andi and Josh at Vanishing Inc. to explore whether such a monster project -- 1200 pages, count 'em -- was something they might consider taking on. In fairness to them they already had an insanely busy publishing schedule, but they were entranced by the idea, and we worked together on bringing the project to life. I have to say that the VI family is incredibly impressive, professional and business-like. A high quality three-volume box set containing so many photos and line drawings (from the exquisite pen of Tony Dunn) requires a not inconsiderable investment upfront, and we'll always be thankful to Andi and Josh for their unwavering belief in this project. I hope they're as proud of the end result as Wayne and I are.

Today he lives in a handsome apartment, depending on benefits to pay for his more-or-less constant care. He runs a modest business that pays him pocket money. Added to which Wayne is still able to perform on-stage, thanks to the help from a number of great friends and carers who surround and support him. He carries the seemingly unbearable burden of his recent struggle to express himself, compromised by his condition which has reduced his speaking manner to a stage whisper, through short, gasping phrases. Despite this, he seems not just unperturbed but almost dismissive of it. This causes Wayne to certainly push himself beyond what you might expect of a disabled person. To the point where he is still putting on an evening show, with Mike acting as his hands, for the public, who clearly adore everything he stands for. So here was a further project for the pair of us: writing a full evening show. His physical condition may have robbed him of his natural speech and articulation, even his comic timing, but they cannot dim his twinkling sense of humour, nor his innate understanding of how to endear oneself to an audience. Nor his sheer gutsiness.

Part of you may well feel saddened about the cruelty of his deteriorating health and the removal it forced of his career as a star performer. Imprisoned though he might be within the confines of his wheelchair, waging his continuous fight with the ravages of MS, totally dependent on others to simply get though the day physically and practically, even today Wayne never fails to carry himself with a certain presence. Like those showbusiness folk who have achieved some stature within their chosen profession, they earn our approval based upon developing a body of work, as opposed to the contemporary fad for a passing, groundless fame.

So whatever else those accursed twin prongs of 'M' and 'S' have robbed Wayne of, it has neither dimmed nor sullied That Certain Something. Wayne is very down to earth and easy with others, as he always has been throughout the time we've known each other. But I believe that part of the trick of our gaining insight into What It's Like To Be Wayne Dobson is to be aware of the context of his life within which he frames his career. This has given him the ability to both live in the present and remind us of his past, warts and all; as you may get to experience from within those 1200 pages, he is prepared to be astonishingly honest and tell stories against himself.

Above all what I see is a continuation of his strong work ethic; his determination to sustain his search for perfection in his work; above all, his refusal to allow his illness to curtail his artistic development. Whatever your take on it, it is this strength that makes Wayne an inspiration to those of us fortunate to be exposed to it. And it's entirely to his credit he'll hate me saying that.

Somehow, through it all, when there was doubt, he ate it up and spit it out; he faced it all and he sat tall and did it his way. Despite everything, he has few regrets, nor a trace of self-pity:

"I've had a great life - and it continues to be great," he insists. "I love my life; I'm happier than I've ever been. I am blessed with so many dear friends and the central place Magic has in my life. I'm content with my lot: proud of the past, but I like to look to the future. I may have MS -- but it doesn't have me; it may have a hold on me, but it doesn't define me."

Read more about Wayne Dobson's Legacy, three book set.

Back to blog homepage

Similar posts on the blog: