Revelation by Dai Vernon

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss (originally published in Genii July, 2008)

"This is the book I have always wanted to write." So begins Revelation, Dai Vernon's companion volume to Erdnase's Expert at the Card Table. Vernon produced the 50 typed pages of his manuscript between 1959 and 1961, by which time he had been inspired and fascinated by Erdnase's seminal text for more than half a century. Despite Vernon's intention to publish the book immediately not unlike Erdnase, Vernon too was in need of the money it did not see print until 1984, when Mike Caveney published it as Revelations.

That publication was met with controversy that has lingered ever since. The legend of Vernon's book had grown to mythological proportions during the more than 20 years of its convoluted pathway to publication. By the time the book reached the light of day, readers were convinced that at least one of its longtime caretakers, Persi Diaconis, had deliberately withheld some of the original content. Multiple factors had contributed to fueling that interpretation, including the long delay in publication; Diaconis's statement in an introduction he contributed to that volume that "We are all sad to see the material we have treasured see the light of day," (Diaconis, in the aftermath of the book's release, was reputed to have bemoaned the fact that he "hated seeing the animals using tools"); the fact that much of Vernon's "work" had drifted out through other sources, both above and below ground, over the years of delay; and as well, the ambitious design of the book itself, which, in a sincere attempt to provide a useful tool for the student, partly served to visually overwhelm Vernon's contributions with a great deal of white space (in the margins in which Vernon's comments were sprinkled), as well as with the facsimile text of The Expert itself.

To serious students, however, Revelations remains vibrant, intriguing, and invaluable. Just as Erdnase's original volume seems to yield fresh gems every time one returns to mine its resistant yet precious ore, Vernon's own additions can still serve as gold to the modern treasure hunters of card craft. In my own current reading, I was pleasantly reminded of a technique I had forgotten Vernon's touches on Erdnase's "Blind Shuffle for Securing Selected Card" that warrants inclusion in anyone's day-to-day technical arsenal (and also works exceedingly well following a Spectator Peek).

Cut to the crimp or rather, to 2007 when publisher Mike Caveney was considering a long-awaited reprint of the 1984 release. Meanwhile, David Ben was consumed with researching all things Vernon for his planned two volume biography (the first volume of Dai Vernon: A Biography was reviewed in the July 2006 Genii). In 2005, sources had given him access to a stunning treasure lode: the original typed manuscript of Revelation, along with not one but two sets of photographs of Vernon's hands. Both sets of photos, intended as illustrations, had been misplaced over the years, significantly contributing to the long delays in the book's original publication.

Given these remarkable resources, Mr. Ben contacted Mr. Caveney and proposed a remarkable new version of Revelation. The missing link between the two collaborators was also, by chance, quickly filled in, in the person of graphic designer Michael Albright who had recently designed The Vernon Touch a lifelong student of magic who had known Vernon since Mr. Albright's adolescence. The team was in place, and the project began.

And what a daunting undertaking it must have been. The collaborators were faced with attempting to integrate Vernon's book, Erdnase's book, not one but two sets of photographs, along with additional items that David Ben had also uncovered, some of which Vernon had intended all along to add to Revelation, others which had the potential to be included, the better to create a unique and indeed unprecedented volume of Vernoniana. The obstacles should not be minimized. There were hundreds of Revelations photographs, none of which were explicitly coded to the text. There were other Vernon photos, often in poor condition, of uncertain origin, depicting tantalizing mysteries. There were pages of hand-written notes. These were materials not only of another time, but born of multiple times. The enormous challenges historical, intellectual, and artistic would be to put it together so as to produce both a worthy tribute as well a lasting, practicable tool.

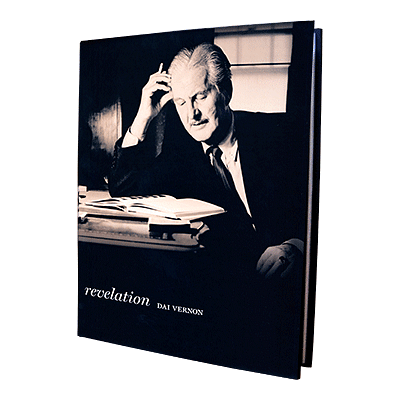

The experience of this book and the book is an experience, an adventure, a wonder begins with an eye-catching dustjacket, featuring two never-before published photographic portraits of Dai Vernon taken by Ross Bertram—Vernon's friend and colleague, and mentor to David Ben. Opening the over-sized volume, the reader is faced with a full-page frontispiece photograph, a close-up image of Dai Vernon's left hand holding a pack in the manner of illustration number two from Erdnase's first technical entry, his system of blind shuffles; overlaying this photo is a vellum sheet imprinted with a perfectly aligned enlargement of the matching Erdnase line drawing. The combined result is a stunningly elegant conception and the ensuing 378 pages are a fitting match for this beautiful entrance.

In an opening publisher's note, Mr. Caveney explains his own involvement with the book's history, offering along the way the surprising fact proven in these pages that not only had "all of Vernon's annotations ... appeared in our 1984 edition," but that furthermore, "additional material from Persi [Diaconis]'s more recent conversations with the Professor" had also been included in the original edition. Rather than content having been excised from Vernon's manuscript, material had actually been added and expanded. Those entries are also included here, but are now carefully distinguished from Vernon's original manuscript by being set within square brackets. The publisher also explains how the book, originally titled Revelation by Vernon, came to be previously released as Revelations, a difference that will, as it turns out, always serve to conveniently distinguish between the two editions.

The designer, Michael Albright, next offers a charming and heartfelt four pages about his personal history with The Professor. Mr. Albright explains that Vernon "showed me how to practice. He taught me the importance of detail. He helped me understand effect from a spectator's point of view." But I think it is important to note, and should become obvious to readers of this volume, that Mr. Albright is not merely speaking of lessons learned about magic. Certainly they were teachings communicated to him in the context of magic, but clearly Mr. Albright has incorporated these lessons into his work as a designer traits he shares, I might add, with his collaborator, David Ben. Vernon was still working on the Diagonal Palm Shift as he neared the end of his life in Los Angeles there are still Vernon moves and refinements from those late days that have yet to see publication. Perhaps Vernon provided a model for the kind of attention to detail that led Mr. Albright to make certain that every illustration in Revelation accompanies its pertinent text on the same page; no page need ever be turned in search of a photograph. I recall Michael Skinner, yet another Vernon acolyte and a legendary sleight-of-hand artist, once telling me that for all that The Professor had taught him about magic, the most important lessons he had learned from Vernon were about life, and how to live it.

There are those who will say that it seems impossible, given the details of Vernon's personal life, that he would have valuable life lessons to offer anyone. This is a foolish and narrow view of the human condition. It has become fashionable in some quarters to take a revisionist view of many aspects of Vernon's life. But in the consideration of art, we must invariably come face to face with the need to "trust the art, not the artist" and to do otherwise is to deny one's self appreciation of much, if not most, of the world's greatest art, since very little of it was ever produced by perfect beings. Who would truly look to the likes of Pablo Picasso or Frank Sinatra as moral exemplars?

It is doubtless true that Vernon was not cut out to be a conventional husband, father, and provider. He, and his family, all paid prices for his obsession and for his genius; his son, Derek, once revealingly said that "As a magician, Vernon was a great magician. And as a father, Vernon was a great magician." But it would be a grave mistake to suggest that somehow these flaws rendered it impossible for Vernon to offer personal strengths and value to a lifetime of friends and colleagues and hence Michael Albright, like Skinner before him and countless others, can offer praise and gratitude for the gifts and guidance they received firsthand. Revelation is a book of instruction in craft and art Erdnase offers that "readers ... should compose their own monologues ... in keeping with their particular personality," purely artistic counsel that Vernon endorses and adds, "should be underlined and imprinted upon the memory." Revelation represents a substantial foundation perhaps even a cornerstone, when we look back on it to the edifice that comprises Vernon's profound influence on the art and craft of 20th Century conjuring.

David Ben's introduction begins: "There is a fine line between passion and obsession." By dint of both, Mr. Ben has become one of Vernon's most important interpreters and historians. And alongside his exquisitely researched biography now stands Revelation as, I dare say, perhaps an equally important and powerful contribution to the Vernon legacy and to future generations of our art. Mr. Ben's 13-page introduction is filled with pertinent details gleaned from his intense study of Vernon's life and work, and includes an array of startling images, inaugurating the parade of visual wonders to follow. Here, for example, is a postcard Vernon wrote on May 11, 1961, to his friend Willis Kenney, announcing that he was in Missouri (at the home of Faucett Ross), attempting to bring Revelation "an analysis and commentary on the Erdnase opus to completion. (In my own research some years ago in the Ken Klosterman collection, I found a letter dated April 16th, a few weeks earlier, that Vernon had written to John Braun, containing similar news: "Am spending a few weeks with my old friend Faucett Ross and we having [sic] been working steadily on a book devoted to a discussion and analysis of Erdnase. This has been tentatively titled REVELATION." Vernon added, "Hope to have it on the market within the next few months.")

Describing his experience of reading the original manuscript for the first time, Mr. Ben observes, "The first thing that struck me when poring through these pages was Vernon's voice." This leads us unmistakably to the next portion of the book: A page-by-page facsimile of Vernon's original typescript manuscript. The decision to include this is a marvelous and insightful choice it is not merely clever design and it certainly is not padding. Although I have read the 1984 Revelations countless times, the opportunity to sit and read the book from first page to last in one continuous piece delivers a radical new vision of the work. Divided merely into footnotes and factoids, one grasps little sense of Vernon's voice or vision. But presented as a whole, one is suddenly taken by the breath and depth of Vernon's passion and personality. Suddenly, one sees it as he intended as an actual book, and what's more, as "the book [he] always wanted to write."

Although Vernon was a capable writer, he never felt compelled to commit his thoughts to the permanent record. He could not have been further in style and personality from the obsessive nature of an Ed Mario, desperate to record every thought as if it was a jewel, unable or unwilling to tell the treasure from the turds. Vernon was more interested in polishing the gems and flushing the rest, and would rather have a session or chase down another hustler than sit at home and preserve the record. Although Lewis Ganson, as Vernon's frequent amanuensis, often failed to grasp the depth and detail of Vernon's work, Vernon found little cause for concern; Ganson was a nice man, hard-working and sincere of intent, and that was good enough.

In this context, it is interesting to note that Revelation was the book that Vernon kept for himself. Lewis Ganson could not have done justice to it; Faucett Ross, though Vernon did not consider him sufficiently sophisticated to share the secret of the Kennedy Center Deal with him, nevertheless was far more capable of helping Vernon to gather his thoughts about Erdnase and record them on paper. (It is also notable in this vein that Vernon wrote the 1941 manuscript Select Secrets himself, and that the description of his top palm dubbed therein as "Topping the Deck"—is the best description extant, despite at least three other significant descriptions in the literature. Vernon's description is now reprinted in this Revelation thanks to the discovery of a set of photographs of Vernon's hands illustrating the move and which now accompany it yet another stellar added value to this production.)

And so, at last, to the body of the book. As Michael Albright said to me, "This is Vernon not Erdnase," and that wise and deliberate prioritization is reflected in Mr. Albright's incomparable design choices. There is no facsimile of Erdnase, as there was in the 1984 edition; there is no reproduction of Erdnase's elaborate title page or humorous preface. However, the entire working content of The Expert at the Card Table has been newly typeset, in a font equivalent to the original; similarly, all the original illustrations are included, albeit that all have been retouched for clarity and cleanliness. This material has appeared before and so, despite its remarkable depth and breadth including Vernon's description of the riffle cull work belonging to "The Mysterious Kid," a.k.a. "Dad" Stevens I shall not take space to inventory it all here. Keep in mind however, that those of us who studied this material in the 1984 edition now get to see it all in an abundance of fresh light, as much of the work from the Stevens cull riffle to the Diagonal Palm Shift is now accompanied by 168 rediscovered, never-before-seen photographs of Vernon's hands illustrating the sleights.

The book's design is built around a flexible but consistent grid, which strives to integrate Vernon, Erdnase, and the astonishing illustrations. That the design reads so effortlessly is testament to the degree of thought and effort that Mssrs. Ben and Albright expended in solving these sizeable challenges. Mr. Vernon's text is always prominent and apparent, set in a more modern sans-serif font than that of Erdnase, and always two-columns wide rather than the single column width of the Erdnase text. The overall style of the design reflects a sense of the time in which Vernon produced his manuscript, namely the late 50s and early 60s. It is a difficult thing to incorporate differing fonts without damaging the look and feel of a book, as well as its readability. That every single photograph in the book the illustrative photographs, the portraiture and other snapshots, and even original Polaroids was individually retouched by Mr. Albright in order to maximize both eye appeal and visual consistency is an all but inconceivable task in itself.

The book is a visual joy a design that is never clever for its own sake, but provides ingenious, tasteful, and sophisticated solutions to genuine problems presented by the content. The results are breathtaking, and the totality of the effect amounts to a profoundly important historical artifact, an essential manual of our craft fleshed out with exciting new discoveries, all delivered in a package that amounts to a publishing objet d'art.

And still, there is more more than 100 pages of newly appended material. It begins with Walter Scott's belly cut, described in Mr. Ben's introduction The bulk of the new content however begins immediately following the completion of the original Revelation, starting with Vernon's work on the cheating maneuver known as "The Spread," including a facsimile of Vernon's hand-written instructions, accompanied by a dozen photographs. This is followed by a "Three-Card Trick for Draw Poker," not a card trick at all but a cheating strategy for partners hustling in a six, seven, or eight-handed game.

The "Cull and Stock" begins with a letter, reproduced here and then subsequently typeset, which Vernon sent to Faucett Ross in 1963. Vernon provides a thorough description of this highly deceptive gambling demonstration of card control. In this, the performer announces his "lucky pair" and then further shuffles the pack. He asks the spectator to name any number of hands, whereupon the performer deals that number of five-card hands. In the course of the deal the performer deals himself the named pair followed eventually by the remaining matching pair, completing the four of a kind on the fifth and final card. Vernon also recounts an amusing tale of how Ed Marlo was thoroughly fooled by Persi Diaconis using both this demonstration, and by his execution of the Zarrow Shuffle in another (unidentified) effect. The letter, from a then 69- year-old Vernon, reveals a bit of the Professor's sense of humor and personality, "...take care of yourself," he writes to his old friend, Faucett Ross, "...we certainly want to be around to see what the boys on Mars and Venus are using in place of the Center Deal and the Parasol Trick."

Next comes "The Hop," a hustler's tabled shift, again provided both with a facsimile of Vernon's notes, a typeset version, and accompanying photos of Vernon's hands. This is followed by the aforementioned reprinted description of "Topping the Deck" accompanied by newly discovered photos of Vernon's hands.

Next is reprinted an extraordinary letter, typed on linen, from Faucett Ross to T. Nelson Downs, reporting a mere four days after the event on Vernon's discovery of the card cheat Allen Kennedy and his remarkable Center Deal. In an accompanying commentary by Karl Johnson (author of The Magician and the Card Sharp, his entertaining and superbly researched history of Vernon's search for the middle deal), Mr. Johnson declares that, "The letter is, immediately, stunning to behold." This is true partly thanks to the remarkable materials a letter and envelope constructed in linen by Vernon's talented wife, Jeanne. But the artifact is also remarkable because, having only recently come to light, it provides yet another unarguable piece of evidence of the facts and timing of Vernon's discovery of Allen Kennedy and his mysterious Center Deal. Those who would, in the face of such timely and incontrovertible exhibits, continue to deny the reality that Vernon indeed met whom he met, learned what he learned, and led the life that he lived, render themselves as stubbornly misguided as those handful among us who would still insist the earth is flat.

Included in this expansive section on the Center Deal is a somewhat comical article that appeared in a pulp magazine called Bold in 1954, recounting "the myth" of the Center Deal and getting most of the particulars wrong. Then the true mechanics of the sleight are presented, first in the form of a reprint of the Ross Bertram description from Magic and Methods of Ross Bertram, accompanied by the photos of Vernon's hands that appeared in the Bertram volume. These photos however have been scanned from the original Polaroids, and further retouched, so their quality is far superior even to the images that appeared with the original description. Following this, David Ben provides seven pages of reflection and commentary on the Kennedy deal, expanding on material he published previously in Genii, and accompanied by 11 additional photographs of his own hands providing details of the technique. For the record, this now comprises the definitive instructive description of the Kennedy Center Deal.

The next segment reprints the classic Eddie McGuire description of the Walter Scott Second Deal, newly accompanied by 11 photographs of Dai Vernon's hands illustrating the technique. There are some readers out there who will now be shaking their heads in wonderment as I was when I first saw the originals several years ago and wiping anticipatory drool from their lips. This chapter concludes with a breathtaking photograph of the famed New York Walter Scott session group, including Downs, Max Holden, Horowitz, McClauglin, Baker, McGuire, Cardini, and a blindfolded Walter Scott.

The following chapter features the Ping Pong Shift, a sleight that has been shrouded in mystery for decades, and appeared above ground in a tantalizing reference in the first volume of David Ben's biography of Vernon; interest was further fueled recently by a description that appeared in the first volume of the Bruce Cervon Castle Notebooks. This segment, and several to follow, is written by Mr. Ben, and I daresay there are few individuals on the scene today who possess the requisite depth and breath of expertise much less the determined curiosity required to piece together the jigsaw puzzle of Vernon's obscure pursuits that this entire project must have presented him with, and that is exemplified in these detailed explorations in the appended material. And so, in the case of the Ping Pong shift, Mr. Ben provides 10 pages of description, accompanied by photos of Vernon's hands photos taken by Jeanne Verner, printed from original negatives which Mr. Ben discovered in his archives attempting to piece together the mystery. Yet one mystery still remains: "Owl Turns Head." I have my own theory about what it means, but readers will doubtless enjoy formulating theirs.

Finally, the appended material concludes with what Mr. Ben has dubbed "perfect the good," his analysis of two sets of photographs, reproduced in the book, of Vernon executing a gambler's tabled shift. Mr. Ben provides his best interpretation of what Vernon might have been doing and why and has produced an extremely deceptive tool in the process that aficionados of such methodology will enjoy studying.

Have I adequately expressed the thrill of this remarkable book? My joy in reading it? My anticipation of savoring it in the years to come? It's true that I am fortunate enough to have paged through the original manuscript of Revelation; I sat across from Vernon as he discussed and demonstrated the Diagonal Palm Shift, and explained why he thought that his notion of twisting the deck after executing the Erdnase Top Palm as described in Revelation wasn't such a good idea after all. But now, the opportunity to read the unabridged text of Revelation in one continuous narrative, to study the Top Palm while seeing the Professor's hands perfectly demonstrating the mechanics one is presented with the next best thing: a personal lesson, the sense of a face-to-face encounter, that reminds me of the times I was that near to him, and may help bring many others, in the years to come, perhaps as close as it is still possible to get. The book is nothing less than a revelation.