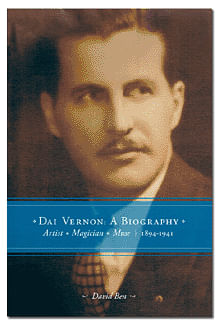

Dai Vernon: A Biography by David Ben

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss (originally published in Genii July, 2006)

In Dai Vernon: A Biography, author David Ben introduces us to a new Vernon, one with whom virtually no reader will be more than superficially familiar. In fact, within the pages of this volume, on y three witnesses to the story are mentioned who are still alive today. Two of them are Vernon's sons, Ted and Derek. For the moment, I will leave it to readers to ponder the riddle of who the third might be.

How could there be a "new Vernon" in light of the fact that Dai Vernon was the most influential and universally acclaimed sleight-of-hand artist of the 20th century? How could there be a "new Vernon" when many remain among us who knew "The Professor" personally, some for decades?

The story described in this first of two planned volumes from Mr. Ben concludes in 1941, with the then 47-year-old Vernon lying in the hospital, and doctors asking him for permission to amputate his gangrenous right arm. Two weeks before, Vernon had taken a job on a construction site, where an accident had plunged him six stories into the East River, thereby landing him in a hospital bed.

Vernon ended up keeping his arms it is chilling to think of the alternative and went on to live to the age of 98.

Thanks to that longevity, most magicians alive today who knew Vernon personally did not in fact meet him until after 1941, and many didn't meet him until decades later. Some met Vernon in New York while still in their youth. Many others came to know him when he moved to Los Angeles in 1963. And there are those who never met Vernon but know him from the writings of Lewis Ganson and Stephen Minch, or from video recordings including the Revelations series. But none of these people knew the Vernon who readers will discover in the pages of this book.

And so, the "new Vernon" to whom David Ben introduces us is, in fact, the historical Vernon—a new figure in the story of conjuring's history. Some readers may find their first encounters with this figure comforting, others may find it challenging, as they compare him with the Vernon they know or think they know. And that comparison will doubtless serve as fodder for much conversation in the months and perhaps years to come.

David Ben brings this new character back from history and very much to life in his marvelous tale. Combining meticulous research, a deep understanding of the workings of magic, and broad insight into magic's artistic history, Mr. Ben turns out to have been an excellent candidate to assume the undeniably daunting task of telling magicians a story of immense importance.

Mr. Ben was certainly not the obvious choice for such a burden; at the time of Vernon's death in 1992, I doubt there was a single person on the magic scene, including Mr. Ben himself, who would have dreamed of such an out-come. Although his magic resume is a stellar one, Mr. Ben met Vernon on only a very few occasions and did not come up in the magic world as a Vernon acolyte. Rather, he was a protégé of another supremely talented Canadian sleight-of-hand artist, Ross Bertram, who knew Vernon but, like many of Vernon's contemporaries, was not an entirely un-critical colleague. It was not until Mr. Ben became involved in a Canadian television documentary, Dai Vernon the Spirit of Magic, that he began to truly fall under the sway of "The Professor."

The amount of independent research that Mr. Ben has engaged in (as briefly attested to by the endnotes to this volume) has brought forth numerous revelations about Vernon's extraordinary life and this book is brimming with such discoveries. No reader interested in the life and work of Dai Vernon will fail to find himself arrested by the revelations of Chapter Three, in which we are privileged to read a firsthand account by Vernon's wife, Jeanne, of her first sighting of her future husband. "This fabulous creature," she gasps, "was Dai Vernon, a slim young man in his late twenties, with coal black hair that grew in an utterly devastating widow's peak and deep set sparkling grey eyes that gave the effect of being lighted from behind, by indirect lighting inside his skull."

Jeanne's articulate voice, never before heard from by the magic community, sparkles with wry wit and intelligence. But that's not all. Before this same chapter is concluded, we also read the words of a Vernon previously unknown to very few but Jeanne herself. In 1923, the usually confident Vernon wrote a love letter that revealed a tentative, besotted young man. "Jeannie my virtues are few, probably negligible," he confesses. "To me, Jeanne darling, you mean everything. ... it is utterly hopeless for me to convey to you the torrent of love and mingled remorse that I sometimes feel." Four months later they were married.

Mr. Ben is no hagiographer and he keeps his eyes wide open as he gazes on Vernon, who is not shown at his best when considered in the light of his family life. His friend, Faucett Ross, would write to Downs that Vernon's "one great mistake was ever to get married," and perhaps the pressures and conventions of the age in which Vernon lived were inescapable; at another time, another place, perhaps he, or Jeanne, might have recognized sooner how poorly suited he was for domestic life. There is no denying Vernon's limitations in this area of his life, and Mr. Ben gives them just attention, but obsession is often the price of genius, and there is genius aplenty—and joy and beauty, too in the Vernon life story.

For Vernon's story truly is the story of 20th century magic, on which he would exert a profound influence. On the aforementioned Spirit of Magic documentary, the late Jackie Flosso, veteran magic dealer and performer, remarked that there is likely not a magician alive who—whether he knows it or not—has not been influenced by Dai Vernon. The statement is likely true, since some of Vernon's broader ideas—of what served to make magic natural, convincing, and artistic can be applied in any branch of the art. But if there is any question as to how much impact Vernon may have left on large-scale stage magic, it is unarguably true that he dramatically trans-formed sleight-of-hand magic in general and close-up and card magic in particular.

One compelling aspect of Mr. Ben's work is his ability to capture the milieu of the magic scene in the first half of the 20th century. At that time, magicians communicated with one another about the latest magic news, developments, and experiences primarily by letter. These men were steady and determined correspondents, and the author's close reading of many hundreds of letters informs his vivid portrait of the times and the personalities. Some readers who have been paying attention may not be entirely surprised by the portrait of the retired T. Nelson Downs as a supremely egotistical character, obsessed with staying connected to the inner circle that Vernon not only moved in but virtually defined by his presence. But many may find themselves taken aback at Mr. Ben's labeling of Faucett Ross, for example, as one of Downs' "sycophants"—along with Eddie McGuire and Eddie McLaughlin, all intertwined in a four-way round robin of correspondence, ever on the prowl for secrets, and often at the incessant urging of Downs. Ross, traditionally regarded as Vernon's avuncular pal, is portrayed here with a cynical side previously undisclosed by history. In a letter to McLaughlin, Ross writes: "I don't expect to get much from Vernon. All these boys are a big disappointment to me in so far as the super-subtle stuff is concerned. Most of their stuff is simply stolen from ancient sources and polished up a bit"

The author utilizes such social and political machinations to set the stage, providing a clearer view of Vernon's indelible contribution to the art and its culture. Show business was transforming, and there were fewer and fewer opportunities for the grand stage shows of the likes of Kellar and Thurston. The new show business was concentrating in cities and being performed in night clubs and small revues. Vernon was at the center of such changes and at one point in his life was one of its premiere professional performers, presenting magic for upscale New York City clientele. His combination of bravura technique and deep expertise yielded a courageous improvisational style that reflected the jazz music of the age and left most other magic stillborn on arrival. At the same time, he was transforming the art as practiced by its amateur contingent, providing more challenging opportunities for exploration and creativity.

Thus was born what David Bamberg referred to as a "modern school of manipulation, in which apparently no moves are made and things seem to happen of their own accord." This was (and remains) Vernon's legacy, and it was ignited in 1899 when, on Vernon's fifth birthday, his father showed him his first trick the secret to which Vernon would discover for himself, but not right away. That secret had to do with options secretly available to the magician, a concept that would deeply inform many of Vernon's unique contributions to magic (the paramount example of which would be his signature "Trick That Cannot Be Explained").

Two years later, Vernon's father gave him a book, Howard Thurston's Card Tricks, which further fueled his new passion, and only a year later Vernon would have the chance to meet Thurston himself an encounter that would surprise and disappoint him. But it was in 1905 that Vernon would buy, with 25 cents of his own money, the book that would seal the course of his life, and hence much of 20th-century magic: Erdnase's Expert at the Card Table. Erdnase was a doorway into the secret workings of card cheating methods, a subject that would fire Vernon's passion and fuel much of the first half of his life in magic. As Karl Johnson points out in The Magician and the Cardsharp (his engrossing 300-page introduction of sorts to the historical Vernon), late in Vernon's life, those who listened to the stories from the aged raconteur he had become could not conceive of the fact that, as Vernon insisted (notably in a telling moment on the Patrick Page audio interview, From the End of My Cigar)—the stories were real. As Mr. Johnson in fact proved in vivid details of the story of Vernon's search for the Center Deal, it was all real. Vernon had actually lived this life, a life still too remark-able for the imaginations of many latecomers to accept as genuine.

By the time Vernon came to New York in 1915, ostensibly to study at the Art Students League, he was already a wunderkind. On his first visit to Clyde Powers' shop on 42nd Street, when Vernon astounded Powers not only with performance but also with an uncanny ability to analyze magic that Powers demonstrated, Powers declared on the spot that Vernon now had entry to the exclusive ranks of the back room. "Young man," Powers declared, "make this place your home. We have a back room; when Kellar or Ching Ling foo, or Houdini, Dr. Elliott or any of these well-known magicians are in New York, they don't stay out in front here, they walk in the back room. This is the inner sanctum. We don't invite our customers back there, only profession-al magicians. You can go back there whenever you like." Vernon had arrived and the New York magic scene would never be the same.

This anecdote is only one of countless such evocative stories that will certainly entertain and fascinate readers. Some, like that of "the trick that fooled Houdini," and even the search for the Center Deal, may already be known, but are told here anew in fresh and sparkling dress. Others are engaging thanks to the thorough back-ground which the author provides, enabling readers to better to understand the fine points of, for example, the famous Walter Scott session in New York City. Mr. Ben endorses the theory of that session, first offered in Jeff Busby's Secrets of the Palmettos, that Al Baker was the culprit who slipped Scott's doctored decks into play, the better to impress Max Holden.

Other adventures are less well known, if at all including the antic saga of Vernon talking Sam Horowitz into taking his place doing Vernon's silent Chinese act for a two-week run at the Majestic Theatre in Paterson, New Jersey, an engagement arranged by Hardeen so that the act could be seen by some important agents. Roy Benson helped Horowitz to pull off the impersonation, serving as the act's supposed manager in order to run the band through its rehearsal paces, a task for which the inexperienced Horowitz was ill prepared but for which the veteran Benson was well suited.

In recounting a wealth of such anecdotes, Mr. Ben has managed to overcome many of the pitfalls of the standard magic biography; this is not merely a dry recounting of facts and figures, dates and names. There is so much to Vernon's story that there is no way he can simply dump all the data onto the page and leave the hapless reader to try to sort it all out. Rather, the author has clearly had to make countless decisions in electing what to present and what to withhold, what to feature and what to discard. The book reads briskly, and this is no mean feat. The fact that he can keep this story moving without getting bogged down in the details, that he can seamlessly reach for a reference from another area of magic or show business in order to provide useful context, repeatedly demonstrates not simply that he has done the research, but rather that he has gained sufficient command of the material to present a fluid narrative the material has not taken command over him.

Attentive readers may find points of disagreement. In the author's recounting of Vernon's discovery of the retired card cheat, "Dad" Stevens. Mr. Ben pronounces Stevens "the most accomplished card cheat of the 20th century," and adds that "Vernon's encounter with Dad Stevens was a pivotal moment in the evolution of magic," but he provides scant evidence for this extraordinary claim. He does provide evidence that Stevens' riffle cull technique "remains the most difficult technique in the realm of card table artifice," but the very fact that it remains such a remote and obscure accomplishment would seem to argue against the hyperbolic notion that in discovering Stevens, "Vernon was like Sir Richard Burton discovering the Kamasutra." After all, many repercussions of Vernon's influence on 20th century magic can be readily inventoried, but there are probably more magicians today doing the Center Deal, and more evidence of even a single use of it under fire, than there are remaining signs of the Stevens Control. While Vernon was fascinated by the cheating techniques he assiduously hunted down, and which in turn deeply informed his conjuring innovations, nevertheless it is in plots like "Out of Sight, Out of Mind," in which the magician discovers a card which is merely thought of by the spectator, and the fluidity and mastery that is required to deliver on such effects, in which Vernon's vision and influence is truly revealed. No single gambling move no matter how fascinating to aficionados can begin to capture Vernon's artistic vision.

The author also stumbles on occasion thanks to a rigid structural conceit. Each of the book's 10 chapters concludes with a deliberate punch, often lingering near cliffhanger status. Frequently the device is successful, as in the tale of Vernon's showdown of sorts in a session with the aging Tommy Downs, in which the two gunslingers, one in his prime and the other past, stare each other down over whether or not Downs was using a gimmick in a legendary coin vanish sequence and one of the men blinks.

But at other times the writer risks overplaying his hand. In concluding his chapter about the Walter Scott session, and recounting how Max Holden had, in his Sphinx column, passed his crown of card mastery from Vernon to Scott, the author quotes Vernon, from a letter to Sam Horowitz, as having written that "I'm among the has been now I'm afraid." Taking the quotation at face value, Mr. Ben then climaxes the chapter in dramatic fashion: "Vernon was no longer the prince of the pasteboards. The king was dead; long live the king." But surely this takes Vernon's remark out of context, for he must have had his tongue planted firmly in his cheek when he made reference to the Holden pronouncement. Holden's judgment may have mattered to the general readership of the Sphinx, but Vernon and his good friend Horowitz knew the shallowness of Holden's expertise in making such proclamations.

The author also chooses a melodramatic conclusion for an otherwise marvelous recounting of the development of Vernon's famed Harlequin Act. After a triumphant run at New York's prestigious Rainbow Room, Vernon allowed himself to be cajoled into bringing the act to Radio City Music Hall. Vernon was an accomplished professional close-up performer when he was in the mood to accept such bookings who now had a successful (and radically original) nightclub act on his hands. But his inexperience allowed him to be talked into putting the otherwise potent act on a stage that was simply too large Radio City seats 6,000. When the booking is cancelled after a few days, Mr. Ben concludes that "It took a special kind of performer to play that stage, one like David Bamberg who had the ability to diffuse love for his audience.... It would have been difficult for Vernon, whose bible had been The Expert At The Card Table, a book for gamblers and cheats in which the author stressed the importance of suppressing emotion over gains and losses. It is hard to diffuse love when your life has been dedicated to concealing regret, anger, and compassion.... Now, the one time he had committed himself emotionally to the goal of standing alone, vulnerable in a spotlight on the world's largest stage, he failed. Vernon had gambled on the Harlequin Act and lost."

Such histrionics are regrettable, and the pseudo-psychology unconvincing. The Harlequin Act, untested and fresh out of the starting gate, had been extended at the Rainbow Room, one of New York's most renowned nightclubs, from an initial booking of two weeks into a 10-week run! This is failure? This is failure to connect with an audience close enough to see the gleam in a performer's eyes? Indeed, Mr. Ben's book should put to rest for all time any doubt that Vernon was an effective professional performer at more than one period in his life. But Vernon was neither the first nor the last performer who, due to simple inexperience, allowed himself to be pressured into putting his act into the wrong venue. And in fact, one has to only turn the page to see the truth that the author himself provides, for the first words of the next chapter quote the professional per-former, Paul Fox, observing that, "It gave me a cold shower when I heard Dai was going to play the Music Hall in view of the size of his effects." Case closed, and hold the violins.

But these are essentially stylistic complaints. The sub-stance and achievement of this work are little marred if the prose is generally workmanlike or occasionally overdramatic; or if the author is sometimes coy with discussion of method, perhaps intending a public readership instead of committing clearly to his audience of magicians. Far more important however is the subtle picture of Vernon the artist that gradually emerges the internal workings of this extraordinary creator. Vernon is not merely some crazily obsessed eccentric who can't hold a job or provide for his family; and he is far more than yet another man highly skilled with a pack of cards or consumed by the methodologies of magic. Rather, he is a deeply complex, passion-ate, and at times joyous man, filled with subtle artistic ideas and sophisticated artistic goals, who indelibly trans-forms his art for all time. Vernon is repeatedly commercially successful, and presented with many more such opportunities, but professional performance holds no interest for him nor does wealth or fame. He makes no money from his original creations neither he nor his heirs ever saw a dime from the "Brainwave Deck," which is still sold in countless quantities today but he cares only about the creative credit, and even then, not to obsessive degree. He works on countless versions and solutions to magical problems, but he sees no need to record any but the very best, and then he keeps looking for better ones still. He lives deeply in the world of the gambler and cheat, but he wishes only to collect and record such knowledge, and then use it for miracles, not malice. Faced with concerns about exposure, he comments simply that "Skill cannot be exposed” Striving to become an artist, he seeks originality above all and recoils from anything that may constrain him or render his work run of the mill. Presented with repeated chances to make a living with magic, he cuts exquisite silhouettes and thinks of them as nothing but a source of income.

The author explains in his concluding notes that it required more than seven years to make this book a reality. Readers will get some hint of how he spent those years by way of his end notes, including several pages of specific source notes and a 15-page bibliography. Based on that material, while one can only hope it will not be another seven years until we see volume two, one can readily guess that it's bound to require at least a few. I look for-ward to that ambitious work, which can still draw on first-hand accounts from a rapidly dwindling number of living witnesses that one hopes time will enable the biographer to capture in his net of research. There we will find out how things turned out for many of the players introduced in this first installment including that one living witness mentioned therein, namely a young Milt Larsen. Larsen, it turns out, along with his brother, mother, and father, William Larsen, Sr., first encountered Vernon in 1941. Stay tuned.