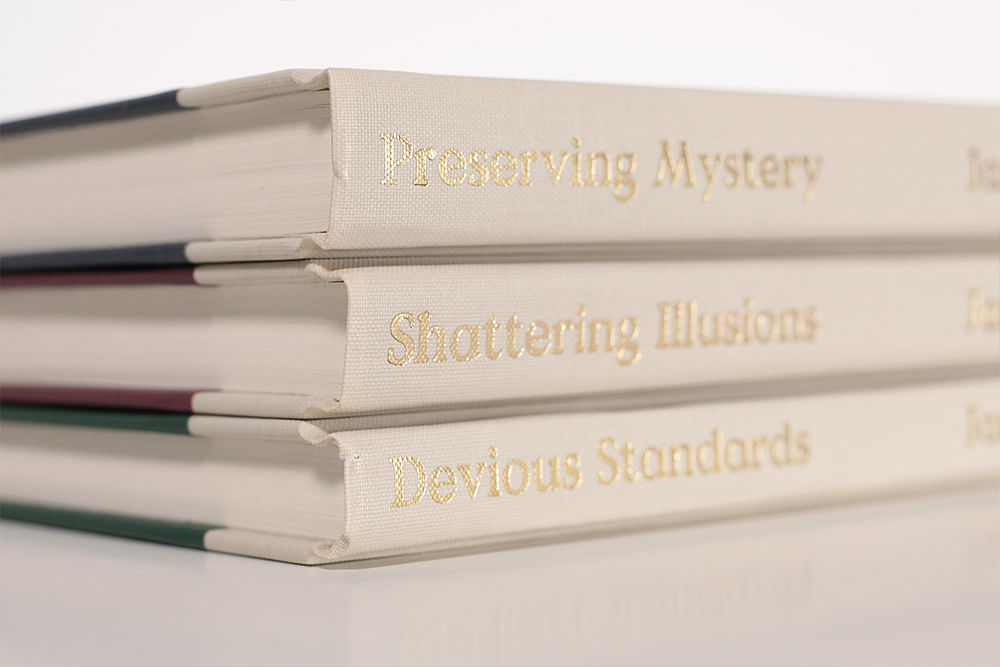

Devious Standards by Jamy Ian Swiss (reviewed by Eric Mead)

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss (originally published in Genii August, 2011)

It's a common misconception that books of essays and magic theory are less valuable in terms of practical knowledge than books that describe tricks and methods. Yet tricks and methods are worthless to one who intends to present them without an understanding of all the theories, small and large, which transform those tricks into theatrical mysteries worthy of an audience. In the opening chapter of Devious Standards, Jamy Ian Swiss presents a strong case that the methods behind illusions, while important, are too often considered the end of understanding required to present the illusion. This may seem obvious on the surface, but reading Swiss's examples it becomes clear that we have seen this error many times, and often from magicians considered to be top performers in the field. When one begins to understand that truly, "the method is not the trick"—not just paying lip service to the idea but really understanding and embracing it as truth—it is no longer mere theory, but supremely practical knowledge. Further, this turns out to be true of a great deal of magic theory, and to dismiss it as less valuable than tricks or methods is to deprive oneself of some of the most useful and stimulating information in the literature.

What, though, of the vast swaths of magic theory that are subjective, debatable, and cannot be said to be true for everyone in all circumstances? Isn't there a lot of so-called theory that is simply opinion? Yes, of course, as it is with any art there are strong and differing opinions about what constitutes best technique, approaches, values, and even what separates the artist from the craftsman from the hack. Swiss acknowledges this many times, never more potently than in his heartfelt and moving remembrance of his friend and mentor Derek Dingle. In discussing a Dingle strategy for the "Cigarette through Quarter" he mentions that Michael Skinner would have hated the strategy, as the two men held diametrically opposed views on a certain aspect of presentation. The implication is clearly that these matters of opinion are important, worth studying and worth thinking about so that we can reach our own conclusions and take a conscious step in the direction of originality and, yes, artistry.

In a lengthy dissertation on the "double lift" and "double turnover" Swiss provides a detailed analysis of the technical demands of the move, the framing and management needed to prepare for the move, exactly why a single technique will not suffice for every conceivable situation, and a comprehensive survey of dozens of possible approaches, with their inherent strengths and weaknesses. Understand that the essay covers 36 pages-36 pages of information about a move that lasts less than two seconds in performance, and even beginning sleight-of-hand performers believe is simple. We are reminded that the most basic and fundamental moves in conjuring are far from simple, and one cannot make decisions about "best practice" with-out understanding all the available options, the history and evolution of the move, and what the differences imply in performance.

Most texts that include an effect requiring a Double Lift simply say to execute the move, with the student left to decide exactly how to do that, or which of the many published techniques is appropriate given the context of the trick. This, as Swiss points out, is precisely why the Double Lift is often butchered in performance—the magician openly lifting two cards at the back of the deck to catch a break, before suspiciously flipping the double card over onto the deck. This kind of approach is not only inferior and inartistic, but will kill the effect of magic for an audience. They may not realize that two cards have been turned over (though they might), but they do see this visible lifting of the cards to get a break, this fiddling with the cards in an open and unmotivated way, and though they may not grasp exactly what is going on, it gives them a sense that the magician is "doing something"—and that small inkling of underlying method is enough to diminish the magical effect. It is only through the kind of deep examination undertaken by Mr. Swiss that this fiddling with the cards is eliminated, that the move becomes invisible and natural looking, and the performance begins to look seamless.

Undoubtedly the chapter that will garner the most discussion and disagreement is titled, "The JS Rules of Magic." Here Swiss lays out a set of 10 rules for better performance. The chapter is full of practical advice, and carefully written so that just when you think you disagree with the edict, Swiss hedges his bet by addressing specific exceptions to the rule that invariably discount the objection. As I began the chapter I couldn't help but think of my own belief that in art there really are no rules that cannot be broken to great effect. I do believe that a beginner, and even most intermediate level performers, should strive to understand the how and why of basic rules before deciding to throw them away at certain times for considered reasons. But I instinctively bustle at the notion of rigid rules for performers and artists to follow. How nice then to discover that after carefully explaining the "JS Rules" and their exceptions, Swiss confesses that the JS in question is not himself but a fictional character from Decremps named Jerome Sharpe. He goes on to admit that he too dislikes the notion of rules in art, and has restated and modified these rules to stimulate thought and discussion—and not in an attempt to codify his own system of standards to be followed.

I mentioned the lovely remembrance of Derek Dingle and didn't want to miss the opportunity to recommend it, and two other personality profiles in Devious Standards as compelling reading. In addition to the chapter on Dingle, Swiss pays tribute to Bob Read and Billy McComb in loving and respectful prose. While these chapters are focused on the personalities, exploits, and artistic importance of three of his heroes, what is equally apparent in the writing is a side of Jamy Ian Swiss that is too often hidden from public view. Far from the aggressive and opinionated personality he's often accused of being, here Swiss is revealed to be a kind, soft, and affectionate friend who sees the best in those he cares about. These men he writes about have deeply affected him as a magician, but also as a human being, and it becomes obvious that whatever else he might be at times, Mc Swiss is an astute observer of character, a passionate lover of good magic, and the kind of friend that good people value.

It should be noted that the contents of Devious Standards are collected and reprinted from their original publication in Genii and Antimony. Even if you have collected them through subscription to those periodicals, Stephen Minch's artistic design and lovely binding make this compact volume a worthwhile investment in having the articles and essays in one easily accessible volume. The finished book is as beautiful as it is challenging, informative, stimulating, and a genuine pleasure to read.