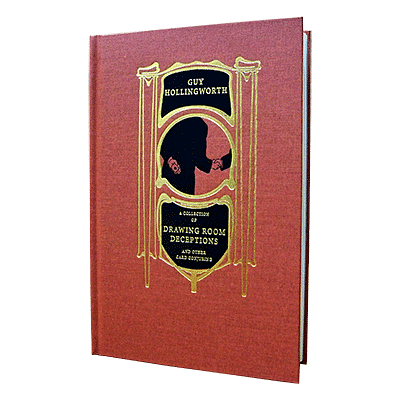

Drawing Room Deceptions by Guy Hollingworth

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss (originally published in Genii October, 1999)

I daresay that few persons reading this esteemed journal are likely to be making their first acquaintanceship with Her Majesty's Obedient Servant Mr. Guy Hollingworth through the services of this columnist's humble musings, and indeed many if not most practitioners of our time-honored art will have been anticipating the arrival of this new volume with bated breath; they shan't be disappointed now that it has reached the shores of these Colonies, so recently and still perhaps wistfully separated from those of our royal protectors. Sorry. I just finished reading Drawing Room Deceptions and the book's style is positively contagious.

Guy Hollingworth is young, handsome, charming, creative, original, a talented writer and illustrator, and possesses killer sleight-of-hand chops—and, despite these obvious traits, most magicians seem to like him anyway, and have greeted his explosive arrival on the magic scene just a few years ago with enthusiastic welcome.

Although it is no flaw, much (although by no means all) of his new book's contents will already be familiar to those who have seen his lectures and his superb videotape, The London Collection, along with his appearance on World's Greatest Magic. Familiar or not, there is an abundance of magic offered in this volume, all of which is well described from an instructional standpoint. In his writing, the author effectively communicates the flavor of his somewhat innately upper-crusty, stiff-upper-lippy, and terribly well-schooled British manner, but also recaptures a sense of a late 19th century, Victorian era volume, replete with a suitable title page, book and chapter sub-headings, stylized drawings reminiscent of the Hoffman period, and occasionally delivering painfully polite language with tongue planted firmly in cheek for just that extra measure of amusement. It's all terribly British, what, and cannot fail to bring a smile to any tasteful reader's lips more than once.

Mr. Hollingworth apparently wrote, illustrated, and designed the book himself, and it is a substantial achievement of taste and talent. That said, one small complaint is that the production values seem not quite up to the level of design; the resolution of the illustration scans seem a bit low, and for reasons that remain mysterious the text appears to have been for-matted to a size different than that to which the book has actually been trimmed, resulting in unevenly oversized margins at the bottom and one side of each page.

There are 23 routines described in essentially seven orderly sections (one trick is deliberately "hidden" in the prologue, and another resides in what is deemed an epilogue), one of which is devoted to an assortment of interesting (if mostly challenging) technical exotica and discussion, including work on the shift, controls, palming, switches (both single and pack-et, tabled and in-the-hand), false deals (seconds, bottoms, and centers) and false shuffles (including Mr. Hollingworth's superb false in-the-hands riffle shuffle with waterfall, which, while it possesses some limited precedent in the Henry Hay Shuffle from the Amateur Magician's Handbook, is significantly superior and one of the finest such techniques extant, and which has in rather short order become a staple of many con-temporary users of the memorized deck).

The first section features "Waving the Aces," which Mr. Hollingworth performed on World's Greatest Magic and for which he has published several versions. This is a standup and quite visual version of Vernon's "Twisting the Aces," which while perhaps not quite as utterly dazzling as Lee Asher's notorious Asher Twist is nevertheless elegantly visual, and includes the benefit of being performed up at chest level where it can be seen by a substantial audience (a subject to which I will return). This is not only one of the best tricks in the book, it is also one of the easiest to execute.

The second section features the "Ambidextrous Interchange," a new plus ultra version of the Jerry Sadowitz plot, possessing an utter purity of effect, a kicker ending (hence the term "ambidextrous" drawn from Larry Jennings's "Ambidextrous Travellers"), and some of the most difficult sleight-of-hand to be published since Earnest Earick's Unseen Forces, and before then probably not since Cliff Green's celebrated and terrifying Professional Card Magic. In fact, if one is previously unfamiliar with this routine, one might well be skeptical that it can be executed at all, much less deceptively performed. However, if you have seen Mr. Hollingworth at lectures, conventions, or via his aforementioned videotape, one must ruefully if admiringly admit that the author accomplishes all of this with breathtaking elan. Duplication of this feat will remain out of reach of all but the most skilled and hard-working; even those capable of mastering this will be compelled to invest many months in the cause. Another excel-lent if challenging routine will be found in the same section, "The Penetration of Cards through the Jacket," in which four Aces, having been lost in a deck that is then pocketed in the side jacket pocket, then visibly penetrate the inside lining of the jacket, followed by the entire deck itself. These two routines depend not only on extreme skill, but—no kidding—upon exceedingly well-tailored clothing. Nothing less than total commitment on all fronts will be required if one truly intends to duplicate the author's impressive results.

The next section addresses a variety of very clever and inventive uses for a gimmick of which the author is particularly fond: the common paperclip. Many will be familiar with his version of the Homing Card, which achieves extremely clean counts of the cards (all the time always concealing an extra) as a result of the device in question. Other applications include a version of the Cannibal Cards and an interesting handling of the Ace Assembly utilizing the MacDonald Ace (i.e., Hofzinser) gimmicks in an atypical (albeit not unprecedented) fashion. Although in some cases one might regard the use of this gimmick as an ingenious solution for a non-existent problem, it is in the area of its application for secret add-ons and clean-ups, via a magnet for holding out cards contained in the paperclip, that the most interesting applications of this principle may lie.

A section of three gambling routines begins with a terrific multi-phase item in which, starting from a new deck, the Aces are repeatedly controlled and dealt, apparently demonstrating a variety of cheating techniques including run-ups and false deals, and climaxing with the return of the unmistakably well-shuffled deck to its original order. Incredibly, this excellent item is not a terribly difficult routine to do, requiring essentially intermediate techniques.

The next section includes a number of routines and ideas that exploit a fascinating principle, namely that of using a bluff signature combined with careful and clever management in order to achieve, in essence, a pseudo-duplicate signed card (in which handling and management enable the conjuror to display the bluff signature to all the audience except the original signer, and the original signature to the signer while keeping it out of view of the audience). While there are precedents for this—the author mentions several, and I would add a trick in Ted Leslie's Paramiracles in which a signed card appears in a previously sealed, empty envelope, and Pat Page's trademarked "Unknown Soldier Card Trick"—there are some superb routines included here, including the author's own pet closer, which should offer endorsement sufficient to whet your curiosity. This trick, entitled the "Cassandra Quandary," presents a wonderful plot in which the magician predicts that the spectator will, under exceedingly fair conditions, choose a card which, in order to render this outcome virtually impossible, is first removed and sealed by the spectator in an envelope (which is then signed for identification); via a deliberate process the spectator chooses a card which turns out to be indifferent and is tabled; the signed envelope is opened only to discover that the card previously isolated within has vanished; whereupon the tabled selection is turned over and discovered to be the previously sealed card. The methods are clever and effective but not terribly challenging, and the routine is accompanied (somewhat unusually in the context of this volume) by a charming and evocative presentation.

The book concludes with "Reformation," the author's gradual restoration of a signed, torn card. The graduated restoration has precedent in, among other sources, a routine performed by Piet Forton in one of his award-winning F.I.S.M acts, Derek Dingle's tabled assembly of the four quarters of a torn card (used by Doug Henning on a TV special) and a trick that David Copperfield performed on a TV special with a rare sports trading card (just to add an extra layer of unreality to a trick that already appears to have lacked a real-world method). Never-the-less, Mr. Hollingworth's trick is a very impressive achievement, for he has indeed developed a real-world solution, albeit that it will require, at very least, months of intensive practice to master. Alternate versions have already been commercially released, including those by Jon Lovick, Wesley James, and J.C. Wagner; although thus far I consider these inferior to Mr. Hollingworth's, readers will now have the opportunity to consider and judge for themselves. Although many others (some of whom the author mentions) have altered, customized, and perhaps improved upon Mr. Hollingworth's fundamental approach, this acknowledgement should only serve to enhance, not diminish, his own special achievement. While it is relatively easy to reverse engineer this trick, once you have seen it, back toward its methodological antecedent, namely the excellent J.C. Wagner method for the torn-and-restored card, such deconstruction should only serve as a tribute and exemplar of what it means to be a creator. I imagine (and indeed have been told by some who were around at the time) that Mr. Hollingworth's early efforts in this plot's direction were unwieldy and inelegant, as one would no doubt guess; yet through a personalized commitment to his own individual vision, in the end the creator won out and saw his creation through to the end. From there, it is far easier to fine-tune and adjust and even improve; no one will ever match, no matter the improvements, the glory of the original breakthrough.

That is quite an impressive list of contents. There is little to complain about concerning this material, other than perhaps the rather minimalist approach to presentation and misdirection—tricks like "Ambidextrous Interchange" and "Reformation" are perhaps best described as being of the "every move's a move" school of cardmanship—but Mr. Hollingworth effectively inoculates himself against such critique by acknowledging in his prologue that, at the age of 24, what can he be expected to contribute to the literature of misdirection or the "deeper inner meaning of magic that has not already been discovered?" I would also observe in passing that when one is possessed of substantial creative and technical skills at such a young age, one is likely to rely far more at first upon brute force ability than upon subtlety or misdirection—witness not only the work at hand but also that of the aforementioned and similarly talented Lee Asher—and that misdirection does seem to be a skill that comes, almost without exception, only with experience and maturity.

That said, what I find most interesting about Mr. Hollingworth's work is in fact a commercial aspect—namely that from the outset he has realized that one of the most difficult set of conditions in which one must perform magic professionally is in the banquet table setting, wherein groups of perhaps eight to twelve people encircle large cables typically laden with huge, sight-line-killing centerpieces, invariably gathered in stupendously large rooms with table upon table of guests, all chattering and eating and making much noise along with the clattering of dishes and the accompanying band, rendering conversation beyond those immediately adjacent to the performer all but impossible, and eliminating (for a multitude of reasons, including sight-lines and surface area) the option of performing on the table itself. The author has addressed these challenges by developing a number of routines which are: (a) performed at chest height, rendering them readily visible; (b) include multi-phase plots that build beyond the one-beat mystery of the card-in-impossible-location variety; and (c) are distinctly visual and hence can be apprehended with relative clarity without a great deal of accompanying verbiage, should the need to jettison such niceties arise. Hence tricks like "Waving the Aces," "Ambidextrous Inter-change," "Cards through the Jacket," and "Reformation" all fulfill these conditional specifications nicely—and this is no mean fear.

Magicians often overlook the fact that Tommy Wonder's signature Cups and Balls routine, which turned out to be one of the most strikingly original versions of our time, was in fact created in service to pragmatic needs, namely the ability to perform the Cups and Balls at restaurant tables without pockets over-stuffed with loads and including automatic reset. That this pedestrian raison d'être resulted in a work of genius is a fascinating subject to contemplate, as is the fact that Mr. Hollingworth's material, while in some cases unspeakably difficult, indeed serves him in similarly real-world fashion. I found this book exceedingly educational and thoroughly entertaining, and whether or not the author's usage of its contents end up serving his readership in like manner remains to be seen—and, I would suggest, is quite beside the point.