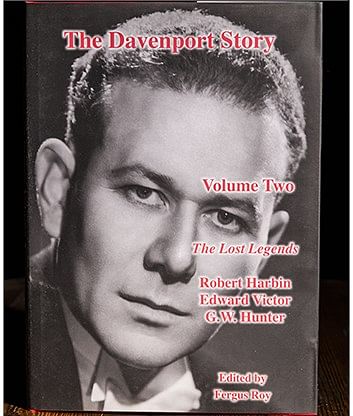

The Davenport Story Volume Two: The Lost Legends by Robert Harbin, Edward Victor, G.W. Hunter

Reviewed by Jamy Ian Swiss (originally published in Genii May, 2010)

In my January column, I reviewed the debut installment of Fergus Roy's The Davenport Story, the first of a planned five-volume series. Hot on the heels of that release comes Volume Two: The Lost Legends. Whereas the previous edition was the first part of the history of the remarkable Davenport family and its magic the story of which will continue in Volume Three the book at hand is something quite different. Lost Legends represents the publication of three long-lost and now rescued works by renowned magic authors and personalities: Robert Harbin, Edward Victor, and G.W. Hunter.

The three authors were all good friends of George "Gilly" Davenport, but in each case, for one reason or another, their books were not published until now. Each work offers a different array of value and charms, and the resulting compendium volume reflects an invaluable and indeed surprising addition to the literature of conjuring like an extra Christmas gift that someone misplaced behind the tree.

Davenport bought the Harbin manuscript in 1946. The immediate postwar period was not a good time to publish such a book, considering paper shortages and other economic factors, but when George Davenport subsequently died, the Harbin manuscript was lost track of for about half a century, until research for the current series of history books led to its rediscovery. Harbin was unhappy that the book never saw the light of day in his lifetime; he expressed his frustration in the introduction to his legendary Magic of Robert Harbin, and warned readers to "watch out for the Lost Book of Harbin." And now the lost book has been found. It's about 100 pages in length, including a reprint of 12 articles, entitled "Twelve Initialed Secrets," that Harbin contributed to Davenport's Demon Telegraph. There are five card items in the first chapter, 14 entries in a chapter of "novelties," 14 items in a chapter of illusions, and three escapes, followed by the "Twelve Initialed Secrets" which represent an assortment of material.

In general, Harbin thought in mechanical terms, and while his mechanical ingenuity is invariably clever, some of the smaller performance props would be anachronistic today, such as a large working vanishing radio, the appearance of which is reflective of the era. The card material and other small magic mostly rely on mechanical apparatus, much of which will no longer hold interest for contemporary audiences. Such limitations must be acknowledged, however Harbin's greatest strength was in his human-scale illusions, and his inventiveness in this arena shows again in these pages. In an illusion entitled "Fifty-Fifty," a woman, and the simple vertical cabinet she is standing in, is cut in half with two solid blades across her waistline, and the top halves of cabinet and woman are slid sideways onto a tabletop. The doors of each half are now opened and both halves of the victim are seen to be quite alive, interacting with the magician. Harbin always had interesting ideas about how to present such illusions as well as how to design them, and he offers that "I do not propose to restore the lady, and intend to leave it at that. My assistant will merely pick up the legs and carry them off, and my lady will protest loudly and hopelessly." This is still an oddball idea 50 years later, and one worth considering.

While some of the other illusions might require some stylistic or cosmetic updating, there are still more good ideas to be found here. The final illusion entry, "The Middle Bit," is actually a rather complex set of interconnected boxes that comprise five illusions performed in sequence. This is probably rather "more clever than good," but still, it's a different sort of idea and one that is fun to think about and potentially thought-provoking for the thinking illusionist (albeit that no doubt some wag might suggest the phrase is currently something of an oxymoron).

Edward Victor was the author of the classic mid-20rh century Magic of the Hands trilogy, published circa 1937 through 1945, and these profoundly influential works remain useful today, to those still inclined to seek resources older than the latest instant download. Victor sold this slim manuscript of about 55 pages to Davenport's sometime before his death in 1964, and it represents a pleasant addendum to his body of work, with descriptions accompanied by Victor's own illustrations. There is elegant and contemporary thinking to be found in its pages, such as the third entry, an application of the Bluff Pass used as a Riffle Force. Victor includes the finesse of, when about to replace the top card as the apparent top half, seizing half the deck in the upper hand and briefly raising it, then dropping the now actual half onto the lower packet with a convincing impact.

I have dealt with the Harbin and Victor manuscripts briefly so as to get to the gem of the package, Mystia, by the professional magician, author, and magic creator, G.W. Hunter. For those interested in the history of stage magic and its great performers, Hunter's Mystia represents a buried treasure now unearthed. Written in about the year 1899, Hunter apparently kept the manuscript to himself for some 40 years, only providing it to Davenport's shortly before his death in 1939. Why the delay7 We don't know for certain, but there is ground for speculation when one considers the book's unusual content.

Mystia (the title is taken from the name of Hunter's wife) is a detailed chronicle of the stage acts and performances of 36 magicians in the late 19'' century not only of what they performed in the music halls and theaters of London and surrounding areas of the United Kingdom, but accompanied by painstakingly detailed accounts of their methods and mechanics. The dispassionate revelations of these inner workings are almost shocking at first blush, and it is easy to imagine as Fergus Roy does himself that Hunter was uncomfortable putting the book out at a time when these performers would have still been alive and perhaps even still working.

Mr. Roy further speculates that in order to obtain the degree of detail Hunter provides, he perhaps with help from his wife, also a performing magician engaged in a certain amount of subterfuge if not outright espionage, using their backstage access as performers to quietly investigate and record such details. It's hard to know if this was really a necessity, since magicians with deep expertise in effects and methods can usually discern a great deal even from beyond the footlights. Regardless of whether or not such lengths were required, Hunter does provide a remarkable variety of information about both performance and the methods by which the tricks were accomplished. Nevertheless, Hunter's efforts seem sincere intended as a contribution rather than a sabotage. Clearly, he enjoyed the intellectual challenge of working out the details of methods, but he was no Ellis Stanyon, offering to sell anyone the secrets to any great performer's act in return for a few pieces of silver. Indeed, there appears to be an underlying respect in Hunter's work; he cautions in his introduction that "This work is not intended to teach the tyro 'how to be a wizard'." He concludes by observing that "my readers will understand, that there is a vast difference, between explaining, 'how it is done' and showing, 'how to do it'."

For readers who have pored over the occasional volume that details programs of magicians' performances such as Magical Nights at the Theatre by Charles Waller (1980) for clues to what experiencing such performances might have actually been like, Hunter's Mystia is a fascinating delight. Mr. Roy reports that when Jay Marshall read the manuscript he pronounced it "one of the most important" works he had read about historic performers, their magic, and methods. Indeed, when reading accounts of the shows performed by names like de Kolta, Maskelyne, Moritt, Kellar, Herrmann and others, it is a worthy pastime to skip the explanations and just read the performances, the better to enable us to strain to imagine what seeing such men on stage was really like. The fact that Hunter sometimes includes the actual spoken words of these performers serves to add further verite to the exercise. I highly recommend the attempt further assisted by a wealth of added photos and illustrations that Mr. Roy, as editor, has drawn from a variety of sources and collections. Hunter's long-awaited Mystia, more than a century after its recording, was well worth the wait, and as well, worth the price of this lovely second volume in the new Davenports historical series.