The History of American Playing Cards

No one knows exactly where or when the first playing cards were invented. To some degree, this is due to minor disagreement about exactly what constitutes a "playing card." Does a playing card have to be printed on paper, or will animal skins, leaves, tree bark, or small slabs of wood suffice? Assuming we restrict our definition to things printed on paper, do the images have to resemble modern cards in the slightest to still qualify as playing cards?

These are perfectly valid questions for serious researchers, but they're beyond the main thrust of this article, which will concentrate on the relatively recent history of American playing cards. More specifically, we'll concentrate on cards from the United States Playing Card Co. (USPCC), dating from the late 19th century to the present. Additionally, our main focus will be on those USPCC products that are of primary interest to magicians.

Before we get into the subject of the origins of playing cards themselves, I'll take a moment to point out one thing that we do know for certain. The standard deck of playing cards that we are familiar with today did not develop from the Tarot. The earliest Tarot decks date from 1440 in Italy, while the earliest modern playing card references are at least seventy years older.

The Evolution of the Deck

So where did the modern deck originate? We know that the Chinese have been manufacturing paper since at least 100 A.D. In the 10th century, they used paper dominos to play games that closely resemble the way modern card games are structured, i.e. with various levels of information that remain concealed from your opponent during play.

To date, the first mention of playing cards in Europe comes to us from Spain in the late 14th century, David Parlet, in A History of Card Games (Oxford University Press, 1991) tells us that they were listed as almost identical to the modern Spanish naipes (cards). Less than four decades later, in 1408, we're given the first written reference to marked playing cards. It may have taken four decades to write about them, but I'll bet marked cards were invented less than four minutes after the first normal deck.

In the late 14th century — 1376 or 1377 — depending on the calendar you use, the earliest known prohibition of playing cards appears in Italy. Also in 1377, in Switzerland, a 52 card pack containing 4 suits of 13 cards each (the numbers 1-10 plus three male court cards) is described by Johannes von Rheinfelden, a monk from Basle.

By the 1380s, several varieties of cards are reported throughout Europe. These decks, depending on locale, contained different numbers of cards, a variety of suits, and even differing numbers of suits. Indeed, some of this compositional experimentation continues to this very day, especially with regard to the number of cards in a pack.

However, by approximately 1480, the suits that have become more or less standard in the modern pack had been established in France. In fact, many of our modern playing card conventions, at least with regard to imagery, can be traced to France. The French are responsible for developing most of the shapes and color schemes that were soon adopted in England and, eventually, the newly established colonies in America.

Although cards were available in the Colonies prior to the Revolutionary War, the best modern researchers are fairly certain that the cards were actually printed in England and shipped over to the Colonies, and were heavily taxed by the crown. It most likely wasn't until after 1776 that American makers began to produce the first paper playing cards in the newly formed United States. Some of these decks were undoubtedly composed mainly of British pasteboards with a newly printed Aces of Spades-minus the despised British tax stamps. Others were produced entirely by printers in the States, beginning just after the war and into the early 1780s, but very little evidence from this time has survived. Many decks from the period exist in unique, or at most very few, examples.

Early US makers from the late 18th to mid-19th centuries include Amos Whitney, Thomas Crchore, Jaraniah Ford, and Caleb Bartlett. Of these, the Crehore decks survive in the greatest numbers, a testament to how well they were manufactured. It's rumored that Benjamin Franklin printed playing cards in his Philadelphia print shop, but no surviving examples have ever been located. He did, however, use playing cards in one of his electrical experiments.

In the Beginning

Although other makers continued to rise and fall from the time of Crehore and Bartlett, the Big Bang" of the playing card universe, as far as most magicians are concerned, occurred on June 28, 1881, in Cincinnati. But we're getting ahead of ourselves here, so allow me to backtrack just a bit.

In early 1867, A.O. Russell, Robert Morgan, James Armstrong, and John Robinson Jr. began operations as Russell, Morgan & Co. Russell and Morgan were the actual printers of the quartet and, together with their partners, began to produce labels, placards, and a variety of promotional items, including calendars and hundreds of circus posters.

In 1880, Russell suggested that the company enter the playing card business, by that time an industry dominated by companies operating out of New York City. Design and production of new equipment began, including a machine that could punch out playing cards rapidly and accurately. On that fateful day in June of 1881, the very first deck rolled off the line and into the waiting hands of Russell, who laughingly remarked, "That pack of cards cost $35,000." The company had twenty employees and the ability to make approximately 1,600 decks per day.

The very first brand produced by Russell, Morgan & Co. was called “Tigers" and was given the numerical designation No. 101. This simple numbering system would be continued with the other early brands, all of which also appeared in 1881. "Sportsman's" were No. 202, "Army" and "Navy" decks were given the designation 303 (first separately and then together as “Army & Navy No. 303"), and finally "Congress" decks were given the designation 404. Numbers 505 and 606 were used a bit later to refer to gilded-edge versions of the Army/Navy decks and Congress decks respectively. The number 707 appears to have been skipped for some unknown reason, but eventually appeared in 1888 as the "Cabinet” brand.

Bicycles Ride In

During the period from the 1850s through the early 1880s, the bicycle evolved from little more than a board with wheels to something more like what we know today: a pedal-powered, chain-driven method of fairly safe transportation. By 1885, bicycling was taking the United States by storm. According to most accounts, the craze lasted just into the early 1900s.

With an eye toward taking advantage of the latest fad, and acting on the suggestion of company employee Gus Berens, Russell, Morgan and Co. produced the first deck of cards under the Bicycle brand name in July 1885. It was called "Fan" and it was originally produced in red and blue backs, with green and brown versions added a bit later. Although the Fan back was the first deck produced under the Bicycle trade name, it was by no means the most popular. That honor belongs to the "Rider” back, which came a few years later, in 1887. Although over eighty more Bicycle backs would be developed, the Rider back design would, over the next 125 years or so, become virtually synonymous with the entire Bicycle line. It has never been out of print and it continues to be the primary card of choice for casual card players throughout the United States.

Depending on which source you refer to, there have been 81 or 82 back designs produced under the Bicycle trade name that are considered, for lack of a better term, “historically official." These backs were produced from 1885 (Fan Back) until 1947 (Leaf Back). They were typically produced in red and blue, but approximately seventeen of the designs were also produced in the aforementioned green and brown variants. The green and brown versions of all of the decks were discontinued in 1927, and specimens are highly prized by modern collectors. In addition to the single-color examples, five of the Bicycle backs were produced with multiple colors. Those backs are Arizona Plaid, Colorado Plaid, Chain, Handlebar, and Saddle. The last three backs were printed only once and never distributed in the US.

Many of the early Bicycle decks, as well as early examples of the other major Russell, Morgan & Co. brands, were packaged in embossed slipcases instead of the now familiar tuck boxes. Additionally, the nicer and more expensive brands were wrapped in paper before being put into either a slipcase or box. This practice, which was common to several of the makers of the time, continued well into the 1900s.

Strangely, not all of the decks produced under the Bicycle brand depict actual bicycles on the back. In the first two decades of the 1900s, as the automobile and its early precursors began to overtake the bicycle as a mode of transportation, the Bicycle brand expanded to include cars in the artwork. And of the 82 official Bicycle backs, 26 don't depict any mode of transportation at all!

World War I saw the creation of four extremely rare Bicycle back designs, known to modern collectors as the "war series" decks. These decks were introduced in 1918 and quickly discontinued when the war ended that same year. They're so rare, I've only seen images of them, and never an actual card.

The period from 1881 to the mid-1920s was an incredibly busy time for the company. In their first eight years in the playing card business, they went from twenty employees and a daily rate of around 1,600 decks, to employing over 600 people and producing 30,000 decks per day. In 1914, a Canadian subsidiary was opened: the International Playing Card Co. in Toronto, Canada. IPCC ran a separate manufacturing plant from the late 1920s until the early 1990s.

The original name "Russell, Morgan & Co." lasted until 1896. From 1896 until 1891, the company name was Russell Morgan Printing Co. In 1891, it was changed to United States Printing Co. This lasted until 1894, when the name became the United States Playing Card Company. Sometimes, the appendage “Russell and Morgan Factories" was included on the Ace of Spades. This was dropped in 1926, and the name has been simply the United States Playing Card Company ever since.

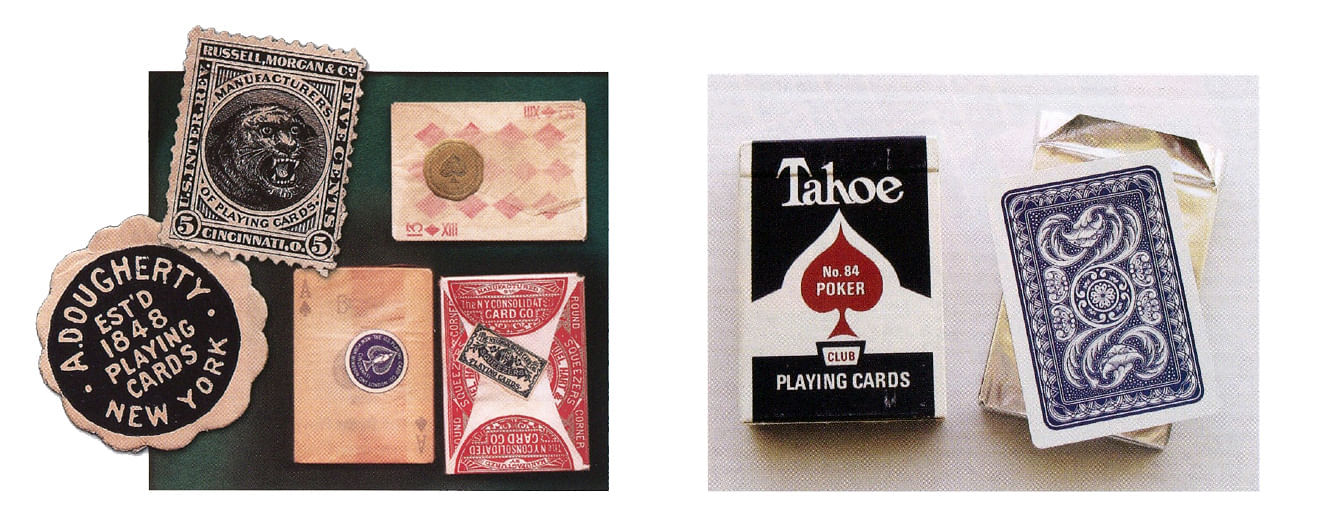

Left: A sampling of old deck seals, including a very early Tiger stamp. Decks were wrapped and sealed in different ways. The Thirteen o f Diamonds card in wax pa per was for the game of Five Hundred.

Left: A sampling of old deck seals, including a very early Tiger stamp. Decks were wrapped and sealed in different ways. The Thirteen o f Diamonds card in wax pa per was for the game of Five Hundred.

Right: The Arrco Tahoe decks were sealed in foil to keep them fresh. Now extinct, they command big money from collectors.

Other Players are Added

In addition to the name changes, USPCC (at that time still technically the United States Printing Co.) began to acquire other playing card manufacturers, beginning in 1893 with the purchase of the National Playing Card Company of Indianapolis.

National had started after a disgruntled but brilliant Russell, Morgan & Co. employee named Samuel Murray left the company over problems with his advancement. Murray had actually designed and installed some of the company's equipment. His departure and the subsequent formation of National were perceived as a serious threat to Russell & Morgan. In March of 1893, National was bought out and Samuel Murray was put in charge of all playing card manufacturing at USPCC. A few brands produced originally by National can still be purchased today, under the USPCC name. Of these, the Aladdin 1001s are perhaps the most popular, although they are not made for the US market.

The years 1894 through 1907 saw the acquisition of several other card manufacturers. The first was the Perfection Playing Card Co. of New York. This relatively minor purchase was followed quickly by the absorption of New York Consolidated Card Co., also in 1894. NYCC was a major player in the card manufacturing world, with roots going all the way back to the 1830s. L.I. Cohen, a stationer from New York City, invented a process for printing four different colors onto a playing card in one pass. After his death, his heirs formed three separate playing card companies, each using his four-color printing process. When pressure from other manufacturers forced them back together, they "consolidated" to form NYCC.

The term “Squeezers” first appeared in the early 1870s and was used as a marketing tool by two of the founding members of NYCC. Prior to 1865, there were no indices in the upper-left and lower-right corners of American playing cards, though a precursor in England possibly existed in 1862. In any case, this idea — which seems, as many great ideas do, completely obvious in hindsight — was first patented in the United States by Cyrus Saladee in 1864. “Squeezers” refers to the fact that the indices allowed a player to keep the cards squeezed together while examining them, rather than having to spread the cards widely and risk flashing one or more to an opponent. From 1873 onward, all playing cards manufactured with indices by NYCC were referred to as Squeezers.

Although it hasn’t been printed in several years, there is still a widely available deck sold under the brand name Squeezers. The back depicts two dogs chained to their respective houses; one of the dogs is named Squeezer and the other is named Trip. “Trip” refers to an invention by manufacturer Andrew Dougherty that was known as the Triplicate. This was an attempt at cashing in on the obviously good idea of the corner index, but without violating the patent issued to Saladee. Triplicate cards have miniature playing cards at the upper- left and lower-right corners. When the cards are held in a tight group, these tiny facsimiles can be read just as if they were a larger fan of normal-sized cards.

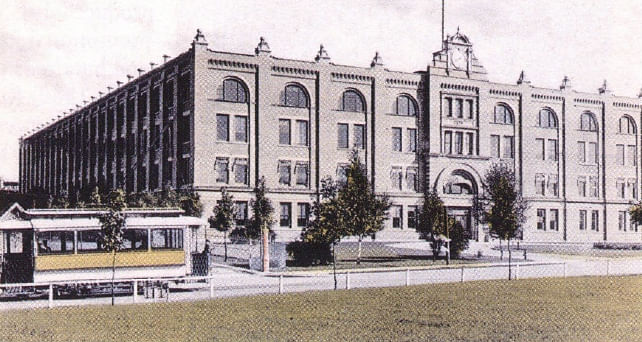

The main building of the US Playing Card Company in Norwood, Ohio, as it looked a century ago.

The main building of the US Playing Card Company in Norwood, Ohio, as it looked a century ago.

After beating each other up for a few years in the marketplace, Dougherty and NYCC decided to divide the US into halves, with each company marketing its products only in its half of the country. As a way of recognizing and honoring this agreement, NYCC created the back design showing the two dogs threatening each other and yet firmly chained to their houses. The printed slogan, “There is a tie that binds us to our homes,” is meant to reflect the fact that the companies were still separate and therefore loyal primarily to themselves, regardless of the pact they’d made with each other. The deck was first issued from 1877 to 1915, reissued at the fifty-year anniversary of the agreement in 1927 and again for the 100-year anniversary in 1977.

Easily the most recognizable brand from the NYCC days is the “Bee No. 92” brand. First released in 1892 (hence the “92” on the Ace of Spades), the Bee brand is still going strong as arguably the paper card of choice among serious card players. It’s also the choice of the vast majority of casinos world wide, where the brand is used for just about every card game except poker, which is played with plastic cards because of their extreme durability.

Most magicians are familiar only with the “Bee No. 67” back, which is the all-over diamond-back design. It’s used primarily for performing gambling-themed routines, as the all-over back design helps to disguise false deals and shuffles. A few magicians have heard of one or two of the older, white-bordered Bee cards, or perhaps have even seen them in antique gambling books or gaming supply catalogs. What magicians don’t generally know is that there have been over two-dozen back designs released under the Bee brand and most of them have had white borders. Those decks are uncommon but not impossible for the observant collector to find.

The last of the really big acquisitions by USPCC was the aforementioned Andrew Dougherty Co. in 1907. A. Dougherty had been an innovator and major seller of cards in the last part of the 19th century. The company held two patents for indices, including the Triplicates mentioned earlier. USPCC operated Dougherty as a separate company until 1930, when it was merged with NYCC and became Consolidated-Dougherty. That name can be seen on the Bee brand Ace of Spades to this day.

Magicians are likely to recognize at least one original Dougherty-factory brand: “Tally-Ho.” Tally-Ho cards were introduced in 1885 (the same year as Bicycles) and are of course still in production today. Although they’re available at most magic shops throughout the US, the Tally-Ho brand was primarily focused on the New York area, and finding them on store shelves outside of that area was (and still is) uncommon. Like the Bee brand from NYCC, most magicians only know of a few of the Tally-Ho back designs that have been produced over the years. Besides the common and still in-print Circle and Fan Back designs, I can think of at least a dozen more. One of them, the very rare “Fox Back” showcases the motif of the foxhunt in a rather uncharacteristically obvious manner, by actually depicting a fox’s head on the back. On modern Tallys, the last remaining traces of the original foxhunt concept can only be seen by looking at the way the Joker is dressed.

Although not as big as A. Dougherty, the purchase of the Russell Playing Card Co. (no relation to the Russell from R&M) gave USPCC the rights to a variety of cards popular with magicians, such as the “Blue Ribbon” and “Aristocrat” brands. Although the Aristocrat brand is still available as a high-end casino card, the ones magicians were mainly interested in were the “bank note” style backs with the beautiful and intricate scrollwork designs. There were several of these backs that stayed in production up until the late 1970s. They’re referred to as “bank note” backs for two reasons. One is that the scrollwork patterns resemble the type of fine-detail patterns found on US currency. The other is that the American Bank Note printing company originally produced them. American Bank Note was bought out by Russell in 1914, then was brought under the banner of USPCC along with the rest of Russell in 1927.

One final brand of cards that is still available today and traces its roots back to the early days of USPCC, and indeed quite a bit earlier, is the “Steamboat” brand. The name “Steamboats” is actually a catchall brand used by many different manufacturers. Steamboats were usually the thinnest and cheapest cards made, and it’s said that they were preferred by gamblers for their all-over back designs. There were probably as many different brands of Steamboats as there were early card printers. The sheer number of different manufacturers makes them a popular subcategory for collecting purposes.

Ace of Spades and Other Collectibles

Speaking of collecting, a major focus of modern playing card collectors is the Ace of Spades. The design of the Ace of Spades is typically a reliable, though certainly not perfect, indicator of the age of a deck. Jokers, which are known to have existed from about 1860 on, can also be helpful. The first Joker to appear under the Russell, Morgan & Co. banner was a Tiger’s head on the 101s. For the Bicycle brand, the Joker first appeared as the “Best Bower” and featured a man wearing a bowler hat and riding a high-wheeled Bicycle. The term “bower” is borrowed from the game of euchre. Some historians also believe that a corruption of “euchre” may have given rise to “juker” and eventually “joker.”

Here’s an interesting piece of historical trivia: the female image on early Russell, Morgan and Co. Aces of Spades is based upon Thomas Crawford’s Statue of Freedom. The statue is atop the US Capitol in Washington, D.C. The current Ace of Spades from USPCC Bicycle cards also shows a version of the statue, which is meant to represent liberty.

Accurately dating any of the decks from the early years of mass production can be difficult. Collectors look at various indicators, including the Ace of Spades, tax stamps, and box design features, but the problem is that not all of these elements remained consistent over the years. Additionally, it appears that decks printed in one year were sometimes, for reasons that aren’t completely understood, released several years later. If you want to try your hand at dating an old R&M or USPCC deck, your best bet is to get your hands on a copy of The Hochman Encyclopedia of American Playing Cards by Tom and Judy Dawson. It is, without exception, the best resource available on the subject.

Although the system isn’t perfect or complete, there is a method that works for dating certain decks manufactured by USPCC, NYCC, and National beginning in 1904. In 1907 and 1929, when A. Dougherty and the Russell Playing Card Co. respectively were bought by USPCC, they began using the same system. The method uses the letter and four-digit codes printed on every Ace of Spades. By looking up the letter code from a rounding the map decks was extremely high given Ace of Spades. By looking up the letter code from a given Ace of Spades, the approximate year of printing, though not necessarily year of sale, can be determined. The difference between year of printing and year of sale is related to the occasional selling of old stock — printed decks — that sat in the warehouse for several years. That wasn’t the standard operating procedure by any means, but it did happen from time to time.

In 1927, to honor Charles Lindbergh’s historic solo flight from New York to Paris, USPCC took a conventional design (known only as “914”) and rebranded it as the “Aviator” deck. The box originally depicted a silhouette of Lindbergh’s aircraft, The Spirit of St. Louis. Today, the popular brand has a jet airplane on the box.

When gambling was legalized (again) in the state of Nevada in 1931, the demand for high-quality cards expanded tremendously. USPCC managed to capture a large share of this rapidly growing casino market and continues to be the industry leader. The majority of casinos prefer the Bee brand, but Aristocrats are also very highly regarded.

When the US entered World War II in December 1941, USPCC aided the war effort by converting much of its production capabilities to making parachutes used to carry anti-personnel fragmentation bombs. They also developed and distributed playing cards that could be used as “spotter cards.” These spotter cards depicted silhouettes of aircraft, tanks, and ships of our allies and enemies. By constantly reviewing these cards, our military pilots developed the ability to recognize friend or foe at a glance. The concept is still used with modern fighter pilots, who often close on enemy aircraft at speeds in excess of 2,000 mph — not enough time for a good long stare.

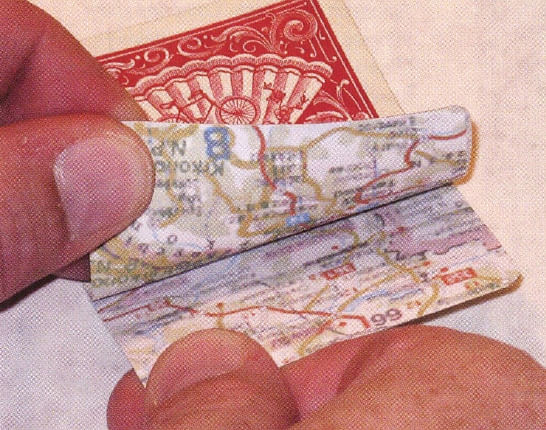

A re-creation of a World War II "map deck" card, which prisoners of war peeled apart to reveal safe routes to freedom.

A re-creation of a World War II "map deck" card, which prisoners of war peeled apart to reveal safe routes to freedom.

Probably the coolest of the card-related items to come out of WWII, and certainly the hardest to find, is known as the “map deck.” It was an idea developed by MI-9, the section of British Intelligence that attempted to assist captured British soldiers. Together with their American counterparts (MIS-X), MI-9 managed to hide maps and other tools in various recreational items that the Germans allowed to reach POWs. One of these items was a deck that included a concealed map of allied escape routes and safe areas. The map was concealed between the layers of the playing cards, which could be soaked in water, then gently peeled apart and the map pieced together.

For political reasons having to do with the prosecution of war criminals, the secrecy surrounding the map decks was extremely high for many years after the war ended. No one knows for sure how many map decks were produced or how many still exist. There is one on display in Washington, D.C., at the Spy Museum. In 1990, USPCC issued reproductions of the map deck and gave them to the surviving POWs of Stalag Luft III. This Luftwaffe-run POW camp was the scene of what later became known as “the Great Escape.”

During the Vietnam War, USPCC again created a special deck just for soldiers. Responding to a request from two Army lieutenants from Company C, Second Battalion, 35th Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, USPCC shipped thousands of “Bicycle Secret Weapon” decks to the troops in Vietnam. Just what was the secret weapon and why was it so secret? The decks contained nothing but Aces of Spades. Supposedly, the Viet Cong thought that the Ace of Spades was a terrible omen of bad luck and would flee at the very sight of it. This story has been largely discredited in recent years, but if the presence of the Ace made the troops more confident in the field, the concept might be considered a sort of “combat placebo.”

Incidentally, the “Secret Weapon” decks were revived for the first Gulf War in 1991. They don’t appear to have been sold in too many places, although I managed to buy several decks on eBay many years later. I’m still not entirely sure what the purpose was, other than an attempt to boost the morale of troops stationed overseas. As a former military member, I can certainly appreciate that, regardless of a lack of any other reasons.

Jerry’s Nugget and Beyond

Toward the end of the Vietnam war, in 1970, USPCC began printing a deck of cards that would go almost completely unnoticed for the next thirty years, but would then find new life on the Internet auction websites. I’m referring, of course, to Jerry’s Nuggets. For those of you who have been living under a rock for the past seven or eight years, Jerry’s Nuggets are ordinary playing cards that routinely sell for upwards of $200 per deck on eBay. According to the Jerry’s fans, there is something “different” about the cards that makes them perfect for certain types of moves and flourishes. Is there any truth to that rumor? Well, as it turns out, there is.

Most modern playing cards have a textured surface embossed onto the paper after they’re printed. This embossing creates tiny air pockets that are not unlike the dimples in a golf ball. These air pockets prevent too much suction from forming between two otherwise smooth pieces of cardstock. After the cards are printed and embossed, they’re coated with a certain type of varnish to protect the paper and provide that slippery feeling that you get from a brand new card. As this varnish wears off, the cards begin to stick and clump together.

Well, it turns out that Jerry’s Nuggets were embossed on only one side — the backs — and used an older cotton-roller press during the embossing. Additionally, they were varnished with what was called a “dip coat.” This particular varnishing/coating process is no longer done at USPCC, at least not in that exact way. Some Internet sources claim that the process was discontinued for environmental reasons, although no good evidence for this claim can be found. Printers’ varnishes haven’t changed that much in forty years.

Those differences in production, however minor they may seem, give Jerry’s their peculiar feel. Just to be clear, the feel of Jerry’s isn’t unique. There were several other casino back designs that were manufactured in that same manner, using identical procedures and paper; these include Golden Nuggets, Carson City Nuggets, and Dunes playing cards. For some reason, these decks, while virtually impossible to tell apart from Jerry’s with your eyes closed, don’t command anywhere near the same prices.

Rare NASA Playing Cards printed by USPCC.

Rare NASA Playing Cards printed by USPCC.

Also, toward the end of the Vietnam war, just as Apollo 14 was about to be launched, NASA asked USPCC if they could provide the astronauts with playing cards that wouldn’t burn in the oxygen-rich environment of the space capsule. USPCC came up with a special “flameproof” paper that just smolders if you try to light it on fire. Don’t ask me how I know that. In any case, my friend Richard Garriott assures me that NASA’s fears were unfounded. Not only did Richard travel into space and return safely in 2008 aboard the Russian Soyuz, but he took regular, flammable-as- all-hell paper playing cards manufactured by USPCC along for the ride. He lived to tell the tale.

In the late 1980s, the United States Playing Card Co. acquired some of the last holdouts in the world that were still in competition with them. Those companies were the Arrco Playing Card Co. of Chicago and Heraclio Fournier in Spain.

The wonderful Arrco “Tahoe” brand cards were of a very high quality and were packaged with an interesting twist on an old idea. Their decks came wrapped in heavy aluminum foil inside the box. This foil wrapping, reminiscent of the paper wrappings used in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, protected the cards until they were ready to be used. Derek Dingle is known to have been quite fond of Arrco Tahoes, and he used them for many years.

Fournier was, and continues to be, the largest playing card manufacturer in Europe. It is one of the few companies to be acquired by USPCC that hasn’t been shuttered relatively quickly. They make their excellent “5 0 5 ” deck to this day, and it is a favorite with many magicians.

In 2001, USPCC bought out Hoyle, a longtime manufacturer based in St. Paul, Minnesota. The Hoyle factory was closed and operations were shifted to the USPCC plant in Norwood, Ohio. USPCC has since moved to Erlanger, Kentucky.

One of the more recent and clever things that USPCC has been involved in is the printing of the “Most Wanted” deck, featuring the top 52 most-wanted terrorists, war criminals, ousted dicta tors, and all-around baddies of the second Gulf War. These decks were created by the Defense Intelligence Agency and naturally they selected Saddam Hussein for the Ace of Spades. The deck became immensely popular with the American public; millions of the decks were printed and sold. As of this writing, fewer than ten of the original subjects depicted remain at large. By the way, I’m not sure what happens if you show a “Saddam” Ace of Spades to a member of the Viet Cong, but I’ll bet it isn’t a pretty sight.

In a move very similar to the “Most Wanted” decks, USPCC recently joined forces with members of law enforcement and the prison system to produce “Cold Case” decks. Each card shows information on an unsolved violent crime, in the hope that someone in the prison system will come forward with information. The idea has already helped to solve several cases.

Finally, in the casino world, USPCC introduced a variant of their popular Bee card, the industry standard for over forty years. It’s called the “Stinger.” Stinger cards have two interesting features. The first is that they have a “faded edge,” which is designed to stop sophisticated advantage players from “playing the turn.” Playing the turn is a legal but frowned-upon technique that allows players to orient the cards during play and then read the orientation of the backs as if they were marked cards. Stingers make this much more difficult. The second feature is the little emblems (usually Bees) that are printed in the four corners. According to promotional literature from USPCC, these emblems are the actual Stingers: they are supposed to make it easier for the surveillance department to spot a false deal. If the Stinger suddenly appears at the edge of the deck, it’s the second card that’s being dealt.

Modern Playing Cards

Now that we’ve covered some of the history of playing cards and the companies that have made them, it’s time to take a look (to the degree that we’re allowed to) at how modern playing cards are manufactured. USPCC is understandably tight with raw numbers, data, and technical details, fearing the possibility of giving away information to counterfeiters as well as legitimate competitors. But what follows is an overview of the process.

It starts with artwork — images. In the past, plates, Photostats, and films were used, but today’s USPCC uses standard off-the-shelf illustration and photo-editing software for their artwork. They then use these files to create and burn the plates for the actual printing and finishing.

The physical production process requires high-quality paper. USPCC doesn’t make their own paper, but they buy it from the best paper manufacturers in the world, and it is made to the company’s exact and proprietary specifications. The two main high-quality paper suppliers today are Koehler in Germany and Arjo Wiggins in France.

Good paper for playing cards must have the proper thickness and content of paper fibers, plus a large amount of “rag content.” Rag fibers give the paper extra strength and “snap.” China clay, casein, and borax may be added to increase the whiteness of the paper and to ensure that the finishing coatings work properly.

The paper comes to USPCC on large rolls, which are fed into a massive (think: hundreds of feet long) machine. This machine glues and laminates two sheets of paper together. The glue is more than a simple adhesive; it is infused with plenty of carbon to ensure that the final playing card is opaque. The amount of pressure used to laminate the sheets is controlled very precisely. The calculations for the final thickness of each playing card even take into consideration how much the printing will cause the cards to swell. It’s a finely tuned operation, to say the least.

The paper is printed with the faces and backs, embossed, and coated with proprietary varnishes. The combination of the level of embossing and the final coatings provides the proper degree of friction between one card and another, as well as between the card and the dealer’s fingers.

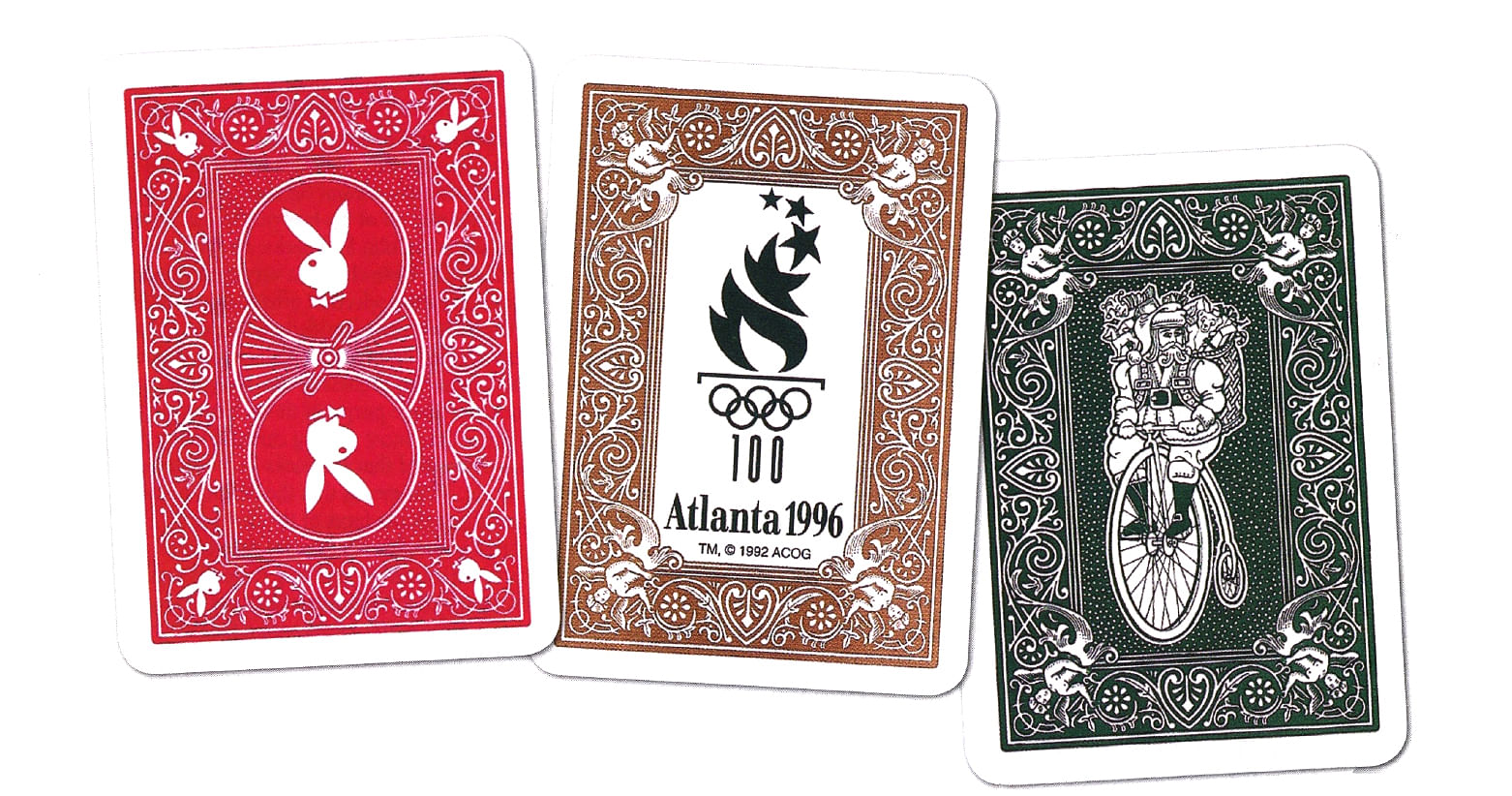

There was a time when the USPCC would agree to alter their trademarked back design themselves, as with these created for Playboy, the Olympics in Atlanta, and the winter holidays.

There was a time when the USPCC would agree to alter their trademarked back design themselves, as with these created for Playboy, the Olympics in Atlanta, and the winter holidays.

After printing, embossing, and coating, the sheets are sent to the cutting machines. First, the cards are “precut” with a large die stamp, then they are fed into a machine that slices the large sheets into eight strips of seven cards each. The cards are then punched out of these strips, one at a time. The punched-out cards are gathered and packaged in the correct order.

Throughout the laminating, printing, embossing, and coating stages, there are various inspection steps designed to ensure that only the best cards reach the market. For some brands, like the Bee casino cards, there are over 200 steps involved in the manufacturing process. Although the following statistic is undoubtedly dated, at one time USPCC official literature stated that only 65 percent of the Bee cards that came off the machines were of sufficient quality to send to their casino customers.

While we’re on the subject of quality control, let’s dispel a rumor: USPCC does not sell lower-quality cards to the big wholesale warehouse chains, such as Sam’s Club or Costco. All of the cards sold in those stores are identical to what you would receive if you purchased a single deck of Bicycles in any grocery, drugstore, or stationery store. It is true that Bicycle produces seconds from time to time that don’t meet their internal standards. And it is true that they sometimes sell these cards. However, they always clearly mark these decks as “Seconds” so that no one is confused about what they’re getting.

At one time, USPCC claimed to be able to make over 250,000 decks per day and over 100 million decks per year. Some sources claim that the machines are/were capable of producing 65 decks per minute. There is no way of knowing just how close these estimates are to today’s numbers, but they’re probably fairly close. One thing that is certain is that the company runs three shifts, essentially around the clock. There is no official word on how many employees work for USPCC, but past estimates of around 750-1,000 are probably accurate.

In the 1980s, USPCC began to allow the manufacturing of cards that altered their trademarked back designs, specifically the Rider back. These cards were usually special orders from outside companies, but as long as they were willing to meet the pricing and minimum order requirements, they were typically allowed to change whatever they wished.

Magicians were also allowed to alter the back designs to suit their needs. Rider back cards with missing or doubled angels, secret markings, or duplicated “edges” of other cards were all allowed and printed. This went on for some 25 years. In the past two or three years, however, the legal department at USPCC has determined that tampering with the back designs weakens the trademark protection that the law affords them. McDonalds can claim a “golden M” as their trademark in the fast-food business, but if they routinely changed the color of the letter, pretty soon they would find themselves losing trademark cases in courts if other people wanted to use a giant M to sell hamburgers. Likewise, if McDonalds tried to use dozens of different typefaces for the M in all of their advertising, they would essentially be undermining their exclusive claim to the instantly recognizable arching M that they use today. The long and short of it is this: if you mess around with your trademark, you weaken it.

So, the word came down a few years ago that USPCC would no longer alter their trademarked back designs or the Ace of Spades. You can still alter the faces of all of the other cards; those are not trade- marked. You can also still get, because USPCC will still print them, any gaffed cards that don’t require the backs or Ace of Spades to be altered. So if you want a double-backer, double-facer, blank-faced, or blank-backed card, it’s no problem. Those cards, and the few other allowable gaffs, will continue to be manufactured in the Rider back. It’s all the others that are now extinct.

A New Back Design

That might’ve been the end of it, were it not for Paul Harris. Paul wanted to have another run of his popular Twilight Angels effect printed by USPCC. When he went to order them a few years ago, he was told that they would no longer print the cards for that trick, because it used altered versions of their back designs.

Paul initially decided to try and come up with another back design that worked equally well, but all his efforts failed. In a phone conversation with me, he said that none of the designs that he tried had that USPCC “look” to them. Something just wasn’t right. Eventually he, along with Tim Trono, Richard Turner, and John Walton, struck a deal with USPCC to design a new official Bicycle back. The goal was to somehow capture the “essence” of the classic Rider back, and also to create just enough of a difference that there would be no problems with altering it. Paul brought on several artists — including Dirk Spece, Gary Bell, and Garrett Thomas — to attempt to capture that elusive Bicycle look.

Did they succeed? I believe they did. The “Mandolin” 809s deck manages to closely resemble the famous Rider back design while having enough distinctive differences to pass any legal challenge that a competitor might try to exploit. If you put the two cards side by side and stand ten feet away, they look like an almost perfect match. The average non-magician or non-card player could probably handle these cards all day and not realize that they aren’t the same old Rider backs. It’s only when you pay attention that the differences become apparent.

And that was the goal all along, to make a card that satisfies all parties: USPCC legal, the magicians who want to alter back designs, and the unsuspecting layperson who will be seeing these cards in magic performances.

Once they had the proper image, Richard Turner began working with USPCC’s Research & Development department to ensure that the 809s were manufactured to the best pos- sible specifications. Richard has been working with USPCC as their “touch analyst” since the early 1990s. The head of R&D at the factory routinely sends Richard batches of cards to evaluate. Over the years, Richard has tested dozens and dozens of different batches; now, he has incorporated all of his favorite design features into the Mandolin 809 decks. For starters, he and USPCC have chosen a very high-quality paper from the selection offered by the mills. Richard has also identified and requested a very specific amount of pressure to use during the lamination process to create a great card for most magic purposes (it’s a teeny-tiny bit thinner than most playing cards). Finally, he has demanded that the decks be traditionally cut. That means that the cutting blades pass through the faces of the cards first. This places a rounded edge on the face of the card, which makes shuffling easier. If you’ve ever tried to faro-shuffle a deck and found that it faros better face up than face down, you’ve found a deck that was not traditionally cut. If the cards faro better face down, like almost all casino cards, then they have been traditionally cut. I’ve handled a deck of Mandolins and I must admit that they feel and shuffle great.

USPCC owns the rights to the Mandolin 809s, but Murphy’s Magic has been granted exclusive worldwide distribution rights. Murphy’s will also coordinate the manufacturing of any new gaffs that require altering the Mandolin back.

Spanning the Centuries

Although I’ve been researching and collecting cards for over a decade, I didn’t actually begin writing this article until June 28, 2010. That’s exactly 129 years to the day that the first deck of playing cards came off the line at what would eventually become the United States Playing Card Company. Nowadays, the majority of cards used by magicians come from USPCC, but whether that’s because the company has control of practically the entire industry or because their product is superior is open to debate. Most likely, it’s a combination of those reasons. What isn’t debatable is that, since their start in 1881, USPCC has produced billions of playing cards. Here’s one author and magician hoping they’re around to make billions more.

Originally written for MAGIC Magazine and published here with kind permission of Stan Allan and Jason England. Jason England is a magician, author, and lecturer currently living in Las Vegas. He has been collecting playing cards for almost twenty years. Images and illustrations provided by: 52+ Joker, Leo Behnke, Steve Bowling, Tom & Judy Dawson, Jason England, Steve Forte, Joseph Pierson, and US Playing Card Company.